Ruins, desolation, the cries of the injured,

and the wails of survivors mourning their lost ones

- this was the scene witnessed this morning in nearly

every town along the Montenegrin coast.

(Perković, 1979, April 15).

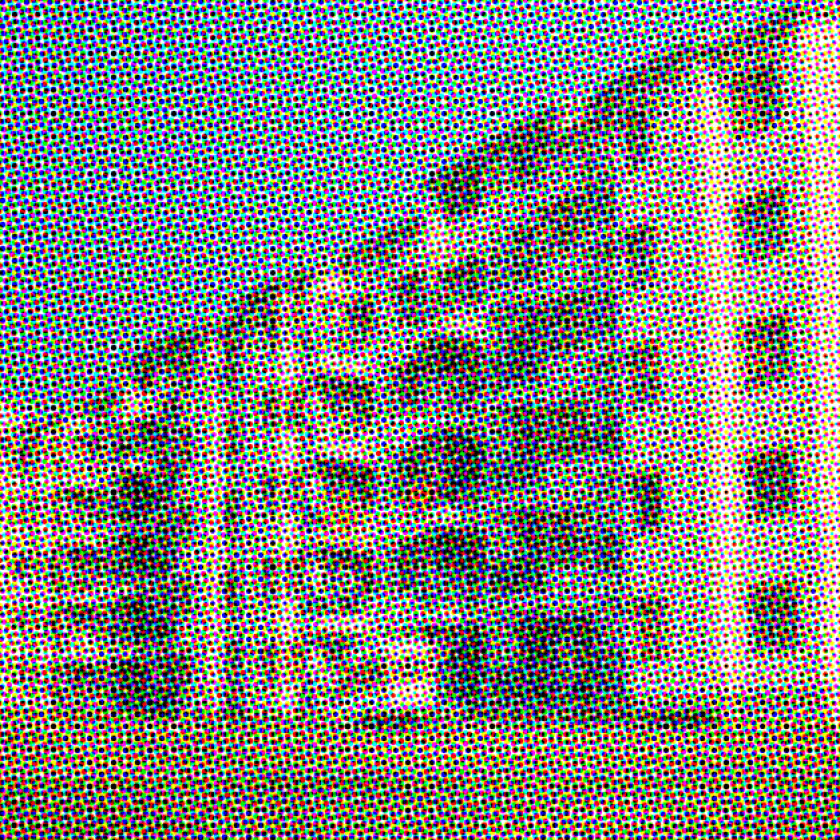

On April 15, 1979, at 7:19 AM, a powerful earthquake struck Bar, Montenegro measuring over 7.0 on the Richter scale and exceeding 9.0 on the Mercalli scale. It caused widespread devastation: homes crumbled, thousands were displaced and significant structures like the “Agava” Hotel1 and the Municipal Court building were destroyed. The Port of Bar, roads, and railways were severely damaged, cutting off the city. The medical center was critically hit, forcing the evacuation of around 300 patients to the hospital courtyard2 (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Municipal Court building, Hotel “Agava”, Port of Bar, Road Bar-Titograd, Hospital. Photographs by Anto Baković and Radio Bar.

Figure 1. Municipal Court building, Hotel “Agava”, Port of Bar, Road Bar-Titograd, Hospital. Photographs by Anto Baković and Radio Bar.

Immediately after the earthquake municipal leaders gathered, a state of emergency was declared, prohibiting entry into buildings. Military personnel enforced a curfew from 6 PM to 5 AM. The railway provided carriages for shelter, and accommodation was available on a ferry. However, many were afraid, trusting only the open sky, they stayed in the fields. Not a single resident of Bar spent the night in their own home (Popović, 1979, April 16).

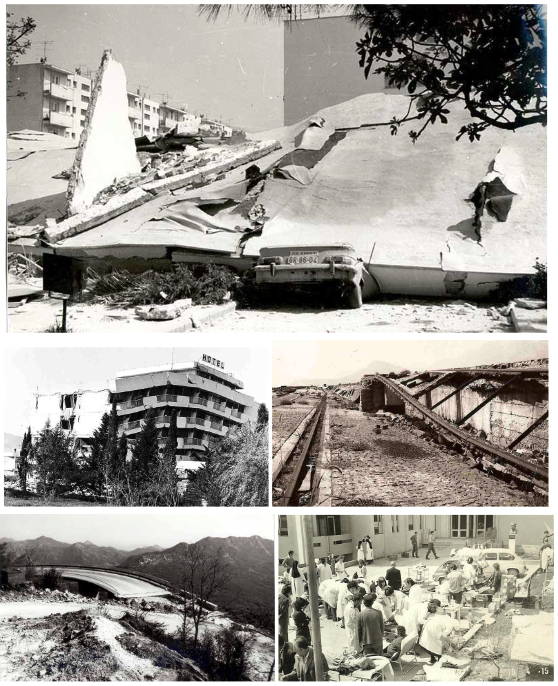

Figure 2. “Emergency session of the Executive Council of Montenegro: The most urgent task - accommodation,” Pobjeda, 16. 04. 1979.

Figure 2. “Emergency session of the Executive Council of Montenegro: The most urgent task - accommodation,” Pobjeda, 16. 04. 1979.

The front page of Pobjeda featured the recovery efforts with headlines such as "Top Priority - Accommodation" and "Solidarity Account," emphasizing the urgent need for shelter and financial support (Figure 3). The town transitioned into a new normal, the municipality, businesses, schools, and the hospital operated from tents while the rebuilding got underway.

Figure 3. “In the Bar Municipality, Brighter Days Amid the Ruins Life is gradually returning to normal, but there remains a shortage of 3,500 small tents. Smiles are slowly reappearing on faces. The Directorate for the Reconstruction of Bar will be established soon. Aid continues to pour in from all directions. / Life under tents: this will soon become a hospital, school, or self-service facility.” Retrieved from Pobjeda, 23. 04. 1979.

Figure 3. “In the Bar Municipality, Brighter Days Amid the Ruins Life is gradually returning to normal, but there remains a shortage of 3,500 small tents. Smiles are slowly reappearing on faces. The Directorate for the Reconstruction of Bar will be established soon. Aid continues to pour in from all directions. / Life under tents: this will soon become a hospital, school, or self-service facility.” Retrieved from Pobjeda, 23. 04. 1979.

On April 21, just six days after the earthquake, engineers from Skopje arrived in Bar to assess which buildings were beyond repair and which could be restored. By April 27, during a municipal assembly session held on the ferryboat Sveti Stefan, anchored in Bar’s port, the Directorate for the Reconstruction of Bar was established, with Čedomir Čejović3 as its director.

With 70 percent of the residential buildings either destroyed or significantly damaged, Bar faced a severe shortage of urban planners, specialists, and construction equipment. Despite these daunting challenges, Bar’s mayor, Blažo Orlandić assured the residents that no one would be left to face the winter in tents or makeshift shelters. Pobjeda captured this commitment with the headline: "Under roofs before winter" (Popović, 1979, April 30).

In early May, work began on the construction of a modern boulevard stretching 1.5 kilometers from the gas station to the future passenger railway station in Bjeliši, marking the beginning of extensive plans for the renewal and development of Bar (Popović, 1979, May 4).

The esteemed Polish architect and urban planner Adolf Ciborowski arrived in Bar that same month. Renowned for his leadership in the post-World War II reconstruction of Warsaw and as the author of the UN-funded "South Adriatic" project (Figure 4), Ciborowski advocated for the construction of permanent solid structures rather than temporary ones.

Figure 4. “Generalni plan Bara” Plan Fizičkog razvoja regije Južni Jadran, UNDP/YU.

Figure 4. “Generalni plan Bara” Plan Fizičkog razvoja regije Južni Jadran, UNDP/YU.

Skopje’s experience with prefabricated structures, still robust after 60 years, offered crucial lessons in urban development. Ciborowski advised that, as in Skopje, temporary buildings in Bar would inevitably shape its long-term growth, and that initial complaints about living under tents would soon be forgotten once permanent housing was in place. Following a visit to Skopje, Bar's delegation learned from reconstruction experts that solid buildings could be constructed as quickly and affordably as prefabricated ones, leading to the decision to build the Makedonsko neighborhood with durable materials.4

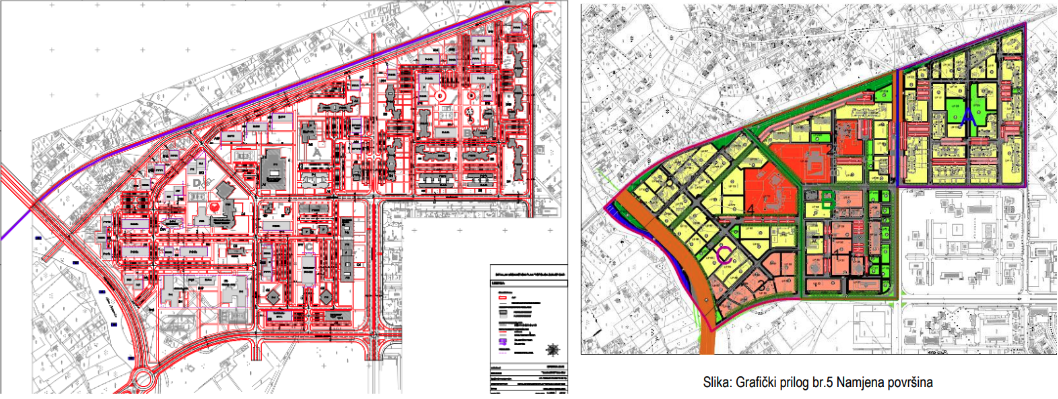

Detailed urbanistic plans were swiftly developed by experts from Skopje, led by architect Krsto Todorovski that aligned with Bar's existing General Urban Plan (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Detaljni urbanistički plan -DUP (Detailed Urban Plan) Topolica-Bjeliši 1979. Retrieved from State Archive, Department Bar.

Figure 5. Detaljni urbanistički plan -DUP (Detailed Urban Plan) Topolica-Bjeliši 1979. Retrieved from State Archive, Department Bar.

The urban planners lived and worked at the “Blažo Jokov Orlandić” elementary school.4 They completed the project in just 40 days, ensuring the rapid development of the new housing neighborhoods. The Detailed Urban Plan for Topolica-Bjeliši designated 15 buildings for collective housing on 7.59 hectares, intended to accommodate 3,312 residents.5 What reduced the design time was also the adaptation of plans from the Aerodrom complex, which was under construction in Skopje at the time. The project specifications for the Aerodrom neighborhood unit A2-2,6 were developed by the company "Makedonijaproekt,"

The detailed urban plan contained nine buildings and defined the typology and distribution of the apartments: 442 units across six typologies (V1, V2, V3, V4, V5, and V6), including 37 one-bedroom apartments, 143 two-bedroom apartments, 193 two-and-a-half-bedroom apartments, 41 three-and-a-half-bedroom apartments, and 28 four-bedroom apartments (Figure 6). The V1 and V2 buildings were designed and constructed with a configuration of a ground floor, two upper stories, and an attic, whereas the V3, V4, V5, and V6 buildings featured a ground floor, four upper stories, and an attic.

Figure 6. Detaljni urbanistički plan -DUP (Detailed Urban Plan) Topolica-Bjeliši 1979. Retrieved from State Archive, Department Bar.

Figure 6. Detaljni urbanistički plan -DUP (Detailed Urban Plan) Topolica-Bjeliši 1979. Retrieved from State Archive, Department Bar.

To facilitate the reconstruction, a public tender was issued, and the Macedonian construction cooperative, that included Pelagonija, Beton, Mavrovo, Ilinden, Trudbenik, Tehnika, and Kozjak, won the bid.

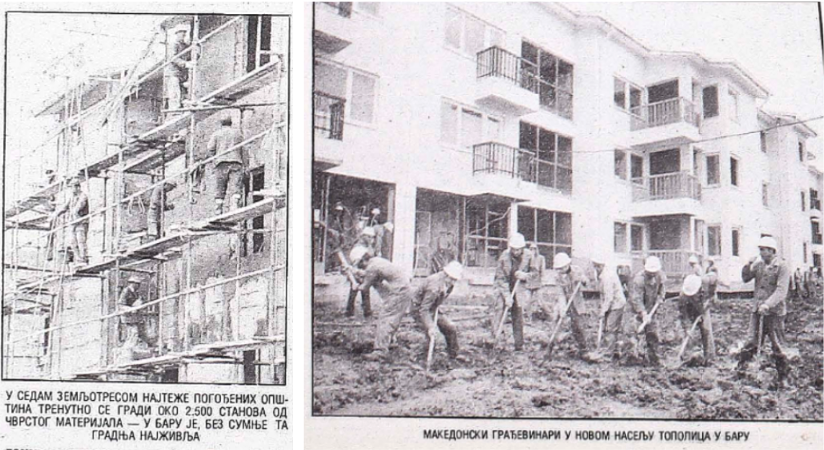

Nearly 2,000 Macedonian workers were involved in building 442 new apartments andrenovating 780 damaged units. Work commenced on August 1, with the goal to complete the renovation of 780 apartments, build 253 new units by Republic Day on November 29, and finish the remaining 90 apartments by the end of January 1980.

Four apartments were built daily under the supervision of engineer Dimče Malinovski, who ensured that all ongoing projects would be completed on time.

"We worked in a highly organized and diligent manner. Our operations were extremely synchronized, following what I would describe as a Japanese timetable,” Malinovski explained in Pobjeda.

The quality of construction materials was rigorously controlled, ensuring that the new Bar neighborhood met earthquake safety standards (Popović, 1979, November 17). Despite challenging weather, workers labored tirelessly, often in three shifts, with night work illuminated by floodlights. The residents of Bar showed deep gratitude, frequently visiting construction sites and bringing food to the workers. In recognition of their efforts, the Bar Municipality named the largest street in the neighborhood “Makedonska.” (Figure 7).

Figure 7. Representatives of the Bar municipality on the newly laid out path for a new street. Retrieved from Orlandić, B., (2002).

Figure 7. Representatives of the Bar municipality on the newly laid out path for a new street. Retrieved from Orlandić, B., (2002).

Figure 8. “Bar Celebrated the 35th Anniversary of Liberation: Farewell to Canvas Roofs A total of 1,800 apartments in the public sector and several hundred individual housing units have been built and renovated. Source: Pobjeda 25. 11. 1979.

Figure 8. “Bar Celebrated the 35th Anniversary of Liberation: Farewell to Canvas Roofs A total of 1,800 apartments in the public sector and several hundred individual housing units have been built and renovated. Source: Pobjeda 25. 11. 1979.

On November 24, the Day of Bar's Liberation, 130 families received the keys to their new apartments. The excitement over the rapid development of the neighborhood was captured in the headline of Pobjeda, which read, "GOODBYE, CANVAS ROOFS" (Figure 8). The article noted: "In the past 35 years, aside from that November 24, 1944, when victorious troops marched into Bar, the city has likely never celebrated its Liberation Day as joyously as this time” (Popović & Vojvodić, 1979).

Figure 9. Makedonsko neighborhood, Rista Lekića street, November 1979. Retrieved from “Kad zemlja podrhtava”, Blažo Orlandić.

Figure 9. Makedonsko neighborhood, Rista Lekića street, November 1979. Retrieved from “Kad zemlja podrhtava”, Blažo Orlandić.

A few days later, on Republic Day, the prestigious AVNOJ Award was bestowed upon the construction company Pelagonija. This significant honor, named after the Anti-Fascist Council for the National Liberation of Yugoslavia, recognized exceptional work achievements, innovative production solutions, and dedicated labor, both domestically and abroad Pelagonija became the first construction organization to receive this esteemed recognition (Figure 10).

Figure 10. Pelagonija building, 1979. Retrieved from “Kad zemlja podrhtava”, Blažo Orlandić.Living at the construction site

Figure 10. Pelagonija building, 1979. Retrieved from “Kad zemlja podrhtava”, Blažo Orlandić.Living at the construction siteAt the end of 1979 and the beginning of 1980, the first residents began moving into Makedonsko Naselje (settlement). Neđeljko7 recalls arriving about six or seven months after the earthquake to find a rough, unfinished construction site. The buildings were surrounded by unpaved areas, scaffolding was still up, and the nearby field was a swamp. The noise of croaking frogs made sleeping difficult, and Macedonian workers were still completing facades and access roads, with puddles and gravel everywhere when it rained (Figure 11).

Figure 11. Builders in Makedonsko neighborhood. Retrieved from Pobjeda 28.11.1979.

Figure 11. Builders in Makedonsko neighborhood. Retrieved from Pobjeda 28.11.1979.

The neighborhood plan encompassed everything necessary for a quality life. In addition to collective housing, the plan included an elementary school, a kindergarten and preschool, clubs, a district library, shops, children's playgrounds, and spaces for rest and recreation (Figure 12).

Figure 12. Elementary school “Jugoslavija,” Preschool, 1984. Retrieved from the film “Bar 84” by RTV Bor.

Figure 12. Elementary school “Jugoslavija,” Preschool, 1984. Retrieved from the film “Bar 84” by RTV Bor.

The school was built with funds from the solidarity of the former Yugoslav republics and began operating on September 1, 1982. “Jugoslavija” has outlived the country it was named after. Despite frequent changes in street names in the region, the school retains its name, preserving the memory of the solidarity and aid from the people of Yugoslavia.

The 1984 General Urban Plan observed that, following rapid post-earthquake growth, Bar lacked valuable green spaces, with the horticultural arrangement of Marshal Tito Street being a notable exception. The plan emphasized the need for future aesthetic enhancements. Nevertheless, the residents of Makedonsko did not wait for official interventions; they took it upon themselves to beautify their surroundings. Zorica,8 a resident, recalls that the greenery around the buildings today is the result of the residents’ efforts. They planted trees, hedges, flowers, and even vegetable gardens to create a pleasant environment.

Figure 13. Makedonsko neighborhood Retrieved from the film “Bar 84” by RTV Bor.

Figure 13. Makedonsko neighborhood Retrieved from the film “Bar 84” by RTV Bor.

Today,9 in Bar, mentioning "Makedonsko" evokes images of a larger area than the initial buildings erected by Macedonian companies after the earthquake. For most, it now encompasses a broader block extending from 24th of November Boulevard to Bjeliši.10

Residents of the buildings attribute their neighborhood's appeal to its vast green spaces, earthquake-resistant structures, and, for some, the basketball courts. Built to withstand an earthquake equivalent to 9 on the Mercalli scale, these buildings inspire confidence. Čedo,11 emphasizes the robust construction and quality, saying he trusts these buildings far more than newer ones, which he believes prioritize business over safety: “I wouldn’t trade my place in Makedonsko for any new building.”

Figure 14. Detaljni urbanistički plan -DUP (Detailed Urban Plan) 2007 (left), DUP 2007 (right). Retrieved from State Archive, Department Bar.

Figure 14. Detaljni urbanistički plan -DUP (Detailed Urban Plan) 2007 (left), DUP 2007 (right). Retrieved from State Archive, Department Bar.

However, the neighborhood is undergoing significant changes, with new urban plans rezoning green spaces for high-rise construction—a trend occurring across the municipality (Figure 14). The late engineer Čejović cautioned that buildings are now being constructed closer together and nearer to streets, often on land originally designated for parking, sidewalks, and green areas, in direct contradiction to urban planning guidelines for seismic regions (Gradnja.me, n.d.).

Čedo acknowledges the city's growth but strongly opposes the loss of green spaces where children once played, lamenting that these areas are being sacrificed for new developments: “They didn’t build it for the city’s benefit but for their own.”11

Today, the Makedonsko community stands as a testament to a legacy of unity and mutual support, reflecting the spirit that once brought citizens together from all Yugoslavia to rebuild Bar. This enduring solidarity is seen at the neighborhood’s beloved basketball courts, where generations have gathered to play, but also to unite for common causes. Prominent basketball stars like Mladen Šekularac and Saša Pavlović honed their skills there. They serve as focal points for charity tournaments, raising funds for medical treatments that benefit people beyond the neighborhood’s borders.

Figure 15. Basketball court in Makedonsko, 2023. Retrieved from Radio Bar.

Figure 15. Basketball court in Makedonsko, 2023. Retrieved from Radio Bar.

However, this cherished space now faces a serious threat. In 2023, the residents of Makedonsko initiated a petition to legalize these courts and revoke the Detailed Urban Plan (DUP) "Topolica Bjeliši," which proposes demolishing them to create parking spaces. The petition highlights the potential loss of green spaces, trees, and a vital community hub, emphasizing the importance of these courts to the neighborhood’s identity and cohesion.

Despite the looming changes, the residents remain resolute in their commitment to preserving the courts they built and maintained for 43 years. For the people of Makedonsko, this struggle is not just about saving a physical space, but about protecting a symbol of their neighborhood's enduring spirit, resilience, and solidarity.

September 2024, Montenegro

Get updates from balkan story map.

Building bio

NEIGHBOURHOOD BIO

Name of the neighbourhood: Makedonsko naselje / Macedonian neighborhood

Former name of the building/neighborhood: N/A

Current Address/District: Makedonska, Požarevačka, Borska, Bulevar revolucije

Period of design:1967

Period of construction:1979-19780

Author/Architect/s/Urban planner: Krsto Todorovski, author of the urban plan Topolica-Bjeliši, Makedonijaproekt architects authors of the building plans

Institution/Architectural studio: Urban plan - Zavod za urbanizam i stambeno komunalna tehnika na SRM-Skopje / Building plans - Makedonijaproekt

Construction company: Pelagonija, Beton, Mavrovo, Ilinden, Trudbenik, Tehnika and Kozjak

The number of buildings: 9

Number of apartments: 442