The capitalist and other classes of ancient origiп

had iп fact been destroyed, but а new class,

previously unknown to history, had been formed.

The New Class (Milovan Đilas, 1957)

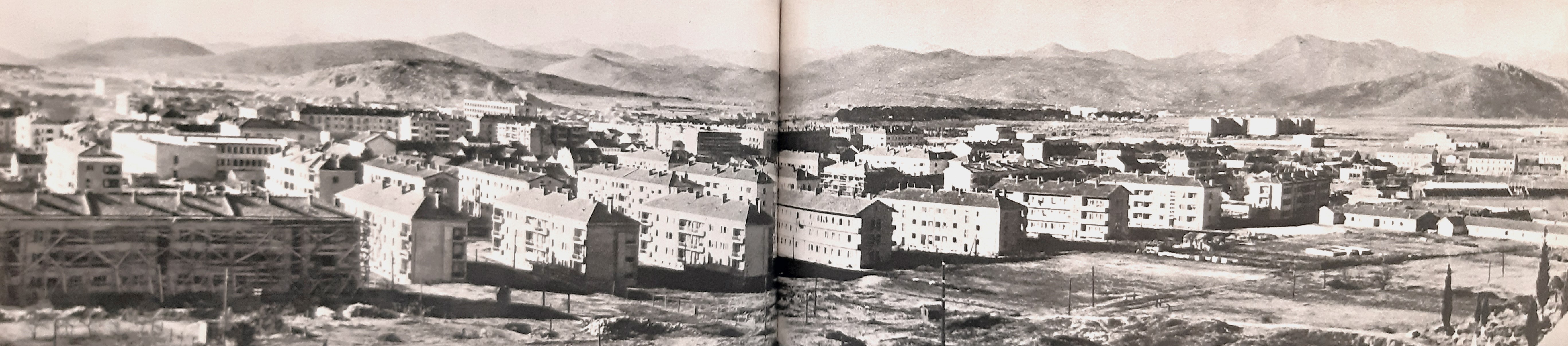

It was July 1946, fulfilling the wish the people of Montenegro and giving recognition to the creator and leader of the Federal People’s Republic of Yugoslavia (FPRY), that the National People's Republic of Montenegro passed the Law on changing the name of the city of Podgorica, the law by which it was renamed Tito(v)grad (Unknown authorship, 1946), (Figure 1). Such a symbolic reflection, rooted in the centuries-long fight against the various enemies and as a recent reminiscing of Podgorica as one of the strongest centers of the anti-fascist movement in Yugoslavia, opened the new path of socialist development enshrined within the city’s identity. Among numerous fields of social transformation, it was particularly conspicuous the influx of the new ideas in the area of design and planning, overtaking thus neo-classical language commonly exercised during the royal era. However, immediately recognized as a powerful tool of representation by the emerging communist elite, architecture also proved to be a fertile ground for experimentation, while at the same time widening the discrepancy margin in an allegedly classless society.

Figure 1. Panorama of Titograd in 1958 - the empty lots in the first plan anticipating the new neighborhood for officials and institutions. Retrieved from Titograd Fotomonografija (Agencija za fotodokumentaciju, Zagreb 1958).

Figure 1. Panorama of Titograd in 1958 - the empty lots in the first plan anticipating the new neighborhood for officials and institutions. Retrieved from Titograd Fotomonografija (Agencija za fotodokumentaciju, Zagreb 1958).

The period between 1960 and 1965 is the most important in the economic development of Titograd, as in this five-year plan the social product and the national income grew fastest in its history (Radević, 1967, p.72). Moreover, this period represents a fundamental sequence for the programmatic development along the general urban plan devised in 1963 and adopted in 1964, after few ambiguous attempts in 1950 and 1957 when several domestic and foreign planners tried to reach a rational strategy for the city’s long term growth. Despite its rigid orthogonal disposition, the plan is often referred to as the “green” plan (Popović, Lipovac, & Vlahović Savić, 2016).It brought a distinctive character, carefully balancing between the major influx of people in the industrialized capital, providing ample space for infrastructure, housing and public spaces on one hand, and the subtle relationship with the natural environment of the city such as parks, hills and rivers on the other. This approach can particularly be appreciated in a subtle urban connection to the hill Gorica both from Nova Varoš in the south and from Zagorič in the north. Along this line, the plan proposed for the first time a clear layout of the resident-administrative neighborhood for the communist party leaders, recognizing the intrinsic values of the southern side of the hill and providing an optimal climatic and functional conditions for its development (Figure 2).

Figure 2. General urban plan adopted in 1964 (left) and actual situation in 1967 with highlighted executive residential neighborhood (right). Retrieved from General Urban Plan Documentation of Titograd, (Milić, 1974).

Figure 2. General urban plan adopted in 1964 (left) and actual situation in 1967 with highlighted executive residential neighborhood (right). Retrieved from General Urban Plan Documentation of Titograd, (Milić, 1974).

While the long term development projections started shaping up on terrain, 1963 was at the same time critical in the context of the new constitutional order in the country. Namely, adopted at April 7th 1963, the highest legislative framework changed the name of the country from Federal People’s Republic to Socialist Federative Republic of Yugoslavia (Službeni list Socijalističke Federativne Republike Jugoslavije, 1963), reflecting the spirit of an overarching Marxist ideology embodied in the so called “death of state”. In other words, the new constitution, at least on paper, made a shift towards more autonomous organization dispersed along the federal units which were supposed to be main progenitors of this socialist democratization process. Albeit the central authority in Belgrade was still considered an overpowering ruling authority, the new constitution also put forward the characterization of socio-political communities attributed to the state members, anticipating more direct connection between the representatives of the political entities and its peoples. In reality this produced the necessity to bolster national party infrastructure and engage recognized party members in charge of smooth execution of constitutional duties amplified with the already existing authority and recognition of those members in each individual republic (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Presidency of the Central Committee of the Republic of Yugoslavia. Josip Broz Tito – President of Yugoslavia (top left), Đoko Pajković – Montenegrin representative (2nd column, 3rd row). Retrieved in 2024 from Gornja Kovačica public facebook group and wikimedia commons.

Figure 3. Presidency of the Central Committee of the Republic of Yugoslavia. Josip Broz Tito – President of Yugoslavia (top left), Đoko Pajković – Montenegrin representative (2nd column, 3rd row). Retrieved in 2024 from Gornja Kovačica public facebook group and wikimedia commons.

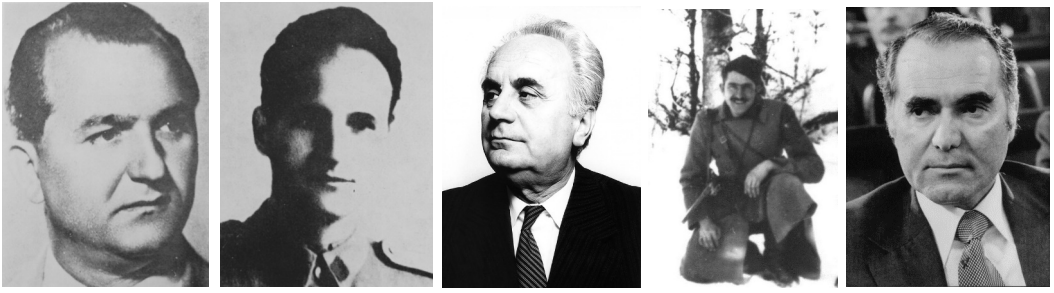

This is when the ongoing developments on national and federal level in 1963 also affected individual career paths of the Montenegrin party officials such as Đorđije Đoko Pajković.1 A prominent member of the communist party, Pajković drew the legitimacy from a distinctive role in the anti-fascist guerilla fights in the north of Montenegro, as one of the founders of the first National Liberation Committee formed in Yugoslavia in July 1941, earning him an award of the Order of National Hero in 1953. After the end of the military career, a significant number of people engaged in other civilian jobs state institutions, mostly in the diplomatic service, internal affairs, but also in as ministers, members of the Federal Executive Council, members of the highest party forums such as the Politburo and the Central Committee etc. (Martinović, 2017, pp.543-658). In the same manner, after serving a high-state duties in Kosovo and Serbia, in 1962, according to the decision of the Central Committee of the Union of Communists of Yugoslavia, he returned to Montenegro, serving as the President of the Executive Council of the Parliament of the SR of Montenegro (1962-1963), while also being the president of the Executive Committee of the Union of Communists of Montenegro (1963-1968) (Gažević, 1976). Consequently, Pajković’s party career path coupled with the need for an effective implementation of the new constitutional duties within the national sociopolitical communities in SR Montenegro, while the executive positions he covered anticipated as effective implementation of the 1963 regulation plan in Titograd, following his political engagement.

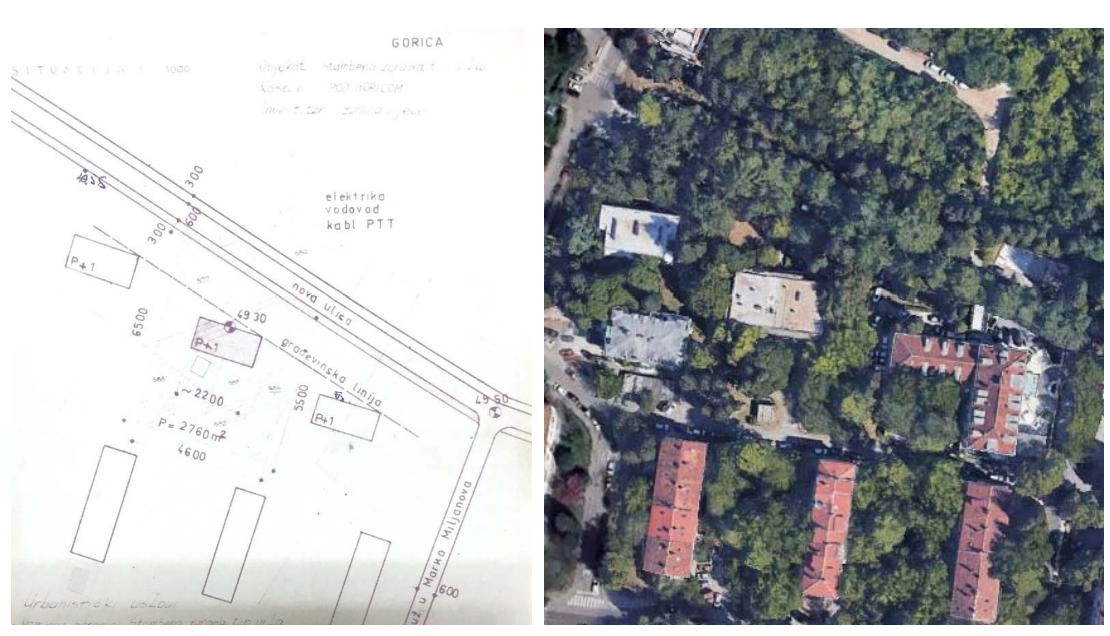

Figure 4. Blueprint of the site plan from the original project (left) and today’s situation (right) of the “Gorica C” neighborhood. Architect: Jovica Milošević, (1963). Retrieved in 2024 from the State Archive in Podgorica and Google Earth.

Figure 4. Blueprint of the site plan from the original project (left) and today’s situation (right) of the “Gorica C” neighborhood. Architect: Jovica Milošević, (1963). Retrieved in 2024 from the State Archive in Podgorica and Google Earth.

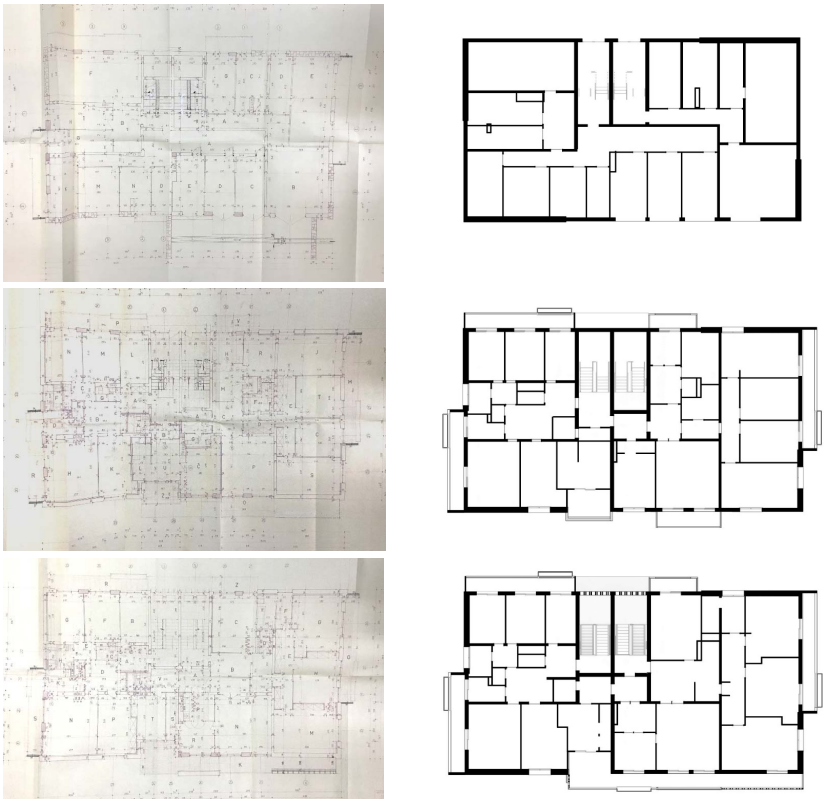

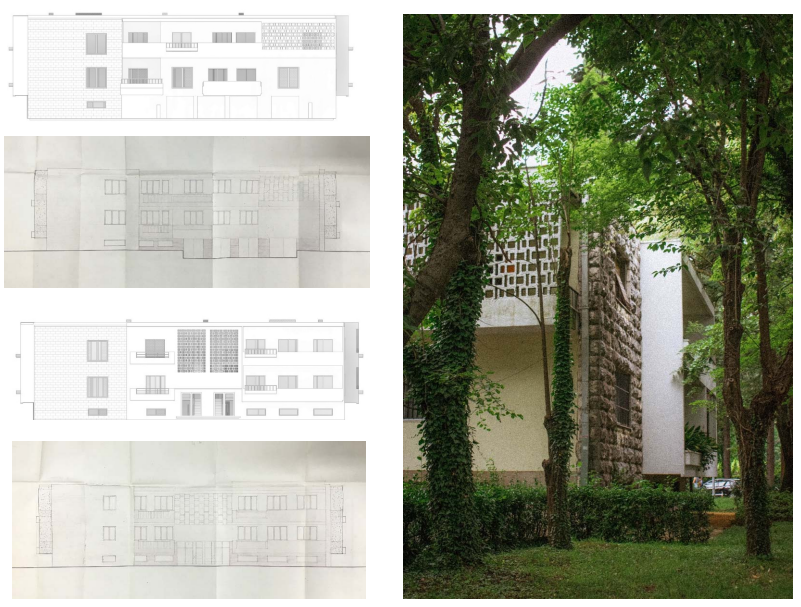

In June 1963, the Executive Council of Montenegro (EC - under the supervision of Đoko Pajković) brought a decision to finance the construction of the residential building in Nova ulica (New Street – today Beogradska street) in the south side of the Gorica hill (Milošević, 1963), (Figure 4). As already anticipated by the regulation plan of Titograd, the area was supposed to accommodate a one-storey building ensemble for the executive bodies, as well as the prominent state institutions. The one financed by EC was the first one to be built among two neighboring households and it was located at the west-end of the street under the so called residential building – type villa (Milošević, 1963). The design project was entrusted to the design bureau of the Organizational construction company “Titograd”2 (Organizaciono građevinsko preduzeće “Titograd”) as one of the most prominent construction companies in the country next to “Provoborac” (Herceg Novi) and “Crna Gora” (Nikšić), while the architect in charge was Jovan Jovica Milošević.3 First, the building urban disposition (2760m2 ) took the advantage of the macro position of the site, with the buffer zone of 10 meters from the street and 20 meters from the neighboring buildings, 4 anticipating the merging with the green belt descending from Gorica hill. Stated as a direct request from the EC, the architect drafted a plan of the building (22x6.5m) with a four-room apartment, one three-room apartment and a studio apartment on the ground floor, and a five-room apartment and a three-room apartment on the first floor. The apartments on the ground floor and the three-room apartment on the first floor are accessed by one staircase (St. no 6), while the fiveroom apartment has its own staircase (St. no 8). In the basement, there are garages, one of which belongs to each apartment, laundry rooms, drying rooms and storerooms for heating equally divided between the households (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Underground floor: garages, laundry, drying rooms and storerooms for heating; ground floor: four-room apartment, one three-room apartment and a studio apartment; 1st floor: five-room apartment and a three-room apartment (top to bottom). Retrieved in 2024 from the State Archive in Podgorica.

Figure 5. Underground floor: garages, laundry, drying rooms and storerooms for heating; ground floor: four-room apartment, one three-room apartment and a studio apartment; 1st floor: five-room apartment and a three-room apartment (top to bottom). Retrieved in 2024 from the State Archive in Podgorica.

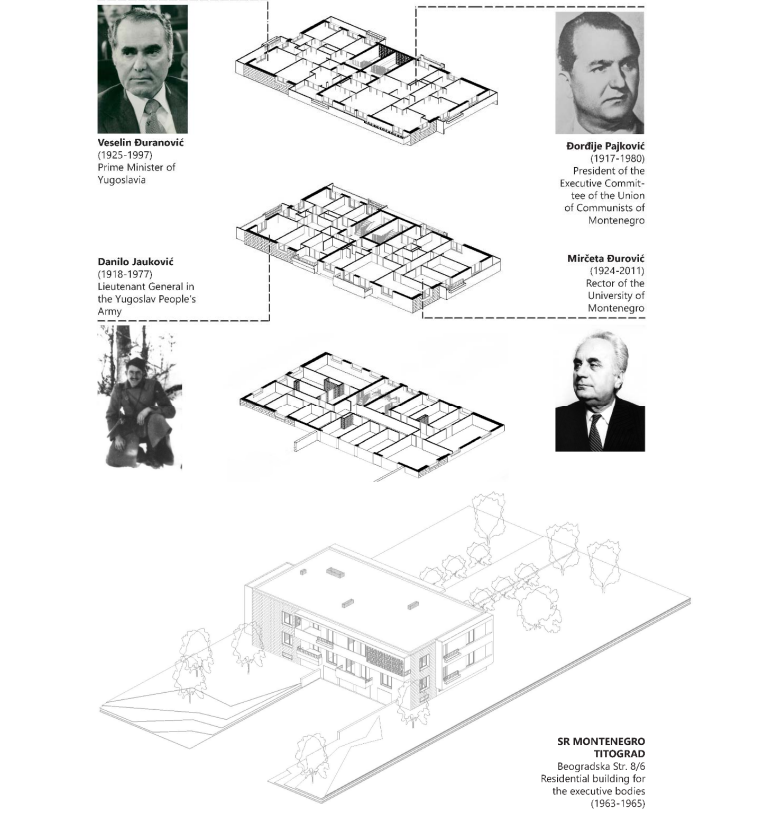

The whole process from the design and construction took almost two years, until finally welcoming first residents by the end of 1965.4 As mentioned before, the five-room apartment was dedicated to the President of the Executive Committee of the Union of Communists of Montenegro Đorđije Pajković after whose death the apartment was given to the Yugoslav Army Colonel Vladimir Božović (1915-2010). Just underneath, the four-room apartment welcomed its first resident General Ljubo Drakić (not identified) who was subsequently replaced by the first Rector of the University of Montenegro doctor Mirčeta Đurović (1924-2011). In the opposite three-room apartment was settled lieutenant general Danilo Jauković (1918-1977) followed by his son, Professor Novak Jauković. Finally, the last apartment was dedicated to lieutenant Đuro Mugoša (not identified) after whom the property was taken by the Prime Minister of Yugoslavia Veselin Đuranović (1925-1997) (Figure 6). Such a diverse background and distinguished authority of the building’s future residents, certainly marked an important bullet-point in the overall design task in front of the chief architect but also an impetus for overcoming the boundaries of the conventional design approach.

Figure 6. Some of the most notable residents of Beogradska 8/6 include President of the Executive Council of Montenegro, Đorđije Pajković, Yugoslav Army Colonel Vlado Božović, First Rector of the University of Montenegro, Mirčeta Đurović, Lieutenant General Danilo Jauković, Prime Minister of Yugoslavia Veselin Đuranović (left to right). Retrieved in 2024 from wikimedia commons.

Figure 6. Some of the most notable residents of Beogradska 8/6 include President of the Executive Council of Montenegro, Đorđije Pajković, Yugoslav Army Colonel Vlado Božović, First Rector of the University of Montenegro, Mirčeta Đurović, Lieutenant General Danilo Jauković, Prime Minister of Yugoslavia Veselin Đuranović (left to right). Retrieved in 2024 from wikimedia commons.

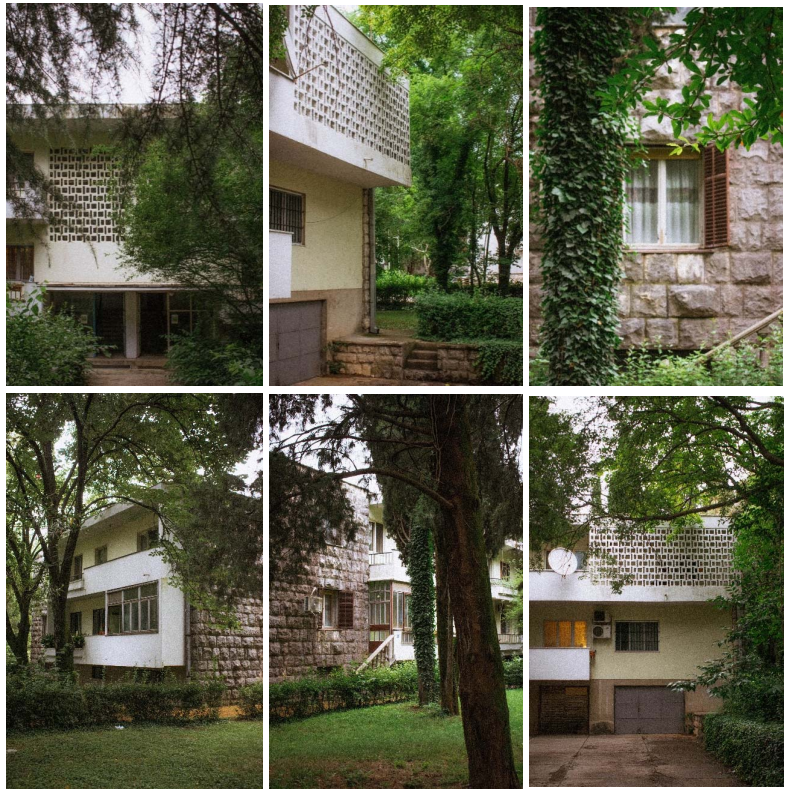

Hence, beside alignment with a quite refreshing guidelines of the new general plan of Titograd, the building introduced an experimental approach both when it comes to the interpretation of typology and composition, as well as the opulence of the living conditions of those for whom it was built. First, residential building – type villa (Milošević, 1963) was a complete novelty in the Montenegrin practice at the time. Following the need to accommodate a distinctive party official such as Đorđije Pajković with its own street number, building entrance, separate garage-apartment connection and detached staircase, while also providing ample space for other distinguished functionaries in the other three apartments, clearly reflected this dual typological characterization or even ambiguity. Thus, the term villa was probably attributed to the lavish design standards for the most prominent resident, while the residential building still echoed the need for a more humbling outlook on the household collective. Second, merging the garage and a living space under the same umbrella was another major step-up in the local architectural practice of the contemporary period in Titograd. Yet again this decision was also conditioned by the living standard among the party leaders, as the level of motorization in the post-war period was very scarce among the ordinary citizens. However, bringing the vehicle on the footstep of the apartments in Beogradska St. 8/6, followed by subsequent examples designed by Vukota Vukotić5 and Milorad Vukotić6 in the same area, made the Corbusian “housemachine” (Johnston, 2001, pp.527-531) concept more distinctively present in the Montenegrin architectural practice. Third, making a subtle transition towards modernist language, which he already deployed quite successfully in the residential buildings in Svetog Petra Cetinjskog St. 15 (1962) and Ivana Milutinovića St. 13 (1963), architect Jovica Milošević made also quite a judicious choice when it comes to composition of the elevations. Namely, proposing a rationalist divisions of the façade surfaces, Milošević uses a local stone embroidery and bright plaster making a subtle connection between the white-modernist and eclectic-classical language, referencing also the practice of the well-known local architect Periša Vukotić.7 This decision is particularly noteworthy in the context in which the political power of the residents in question needed also to be reflected through the materiality rooted in the popular stone-craft tradition in Montenegro, while at the same time lingering on a more progressive spirit of the socialist order (Stamatović Vučković & Bulatović, 2024). In addition, while omitting any kind of decorative pattern application on the facade, the entrance and the terrace of the Đoko Pajković’s apartment were outlined by a specific brickbind perforated pattern covered with white mortar reflecting at the same time the need for protection from the sun and the emphasis on the entrance part (Figure 7). This practice was later popularized in a number of residential buildings both in Beogradska St. as well as in the neighborhoods on the west bank of river Morača. Thus, the robust image of the authority made the compromise with the pragmatic sequences of an innovative design approach, successfully communicating power-relations through the means of the complex architectural composition sharply standing out from the already established design practice within the country.

Figure 7. South elevation (top left) and north elevation (bottom left); corner detail of the building: stone, plaster and brick-pattern. Blueprint of the elevations from the original project. Architect: Jovica Milošević (1963). Retrieved in 2024 from the State Archive of Montenegro in Podgorica.

Figure 7. South elevation (top left) and north elevation (bottom left); corner detail of the building: stone, plaster and brick-pattern. Blueprint of the elevations from the original project. Architect: Jovica Milošević (1963). Retrieved in 2024 from the State Archive of Montenegro in Podgorica.

However, living in such a lush conditions profusely supported by the state benefits, the building in itself also represented a stark reminder of the growing inequalities of the socialist society. Namely, with the apartments reaching almost a triplesize of an average communal family apartment in Yugoslavia of about 55 square meters (Dobrivojević Tomić, 2023, pp.89-103) paved the way for an already well-established social stratification. This was further intensified by the slow rate of construction throughout the country with the imbalances relying on the practice during which the most skilled workers of the construction companies were usually assigned with easily repayable conditions while others have to seek for their private funds. This is where the discrepancy between ideology and practice was probably most palpably anticipated by Montenegrin dissident Milovan Đilas in his book „The New Class“ from 1957. Already in its early stage the author recognized the deffects of the „new class“ hаving special privileges аnd economic preference because of the administrative monopoly they hold stating that “In the Communist system where thе power аnd the government are identical with thе use, enjoyment, аnd disposition of almost all thе nation's goods - hе who grabs power, grabs privileges аnd indirectly grabs property” (Đilas, 1957, p.48). This can be vividly represented in the gradual dispersion of the ownership rights from the state to the individuals in Beogradska St. over time. While the constitution from 1963 in a certain sense initiated the construction of the 8/6 building, the one that came almost ten years later in 1974 reflected a discharge of the unionist clamps, directing the ownership rights over the federal properties towards the individual republics(Anđelković, 2024). In practice, this made the way for further appropriation over the state owned property and gaining full momentum in another round of constitutional changes in 1992, which finally closed the cycle ending in privatization at a bargaining price.

Figure 8. Beogradska St. 8/6, photographs taken by Selma Bulić in 2024 in Podgorica.

Figure 8. Beogradska St. 8/6, photographs taken by Selma Bulić in 2024 in Podgorica.

Finally, the 8/6 building in Beogradska St. presents an ambiguous amalgamation of the Montenegrin history within the socialist development wretched between the ideas of equality and prosperity on one side and harsh discrepancies present in the socio-political disagreements as well as the everyday life of its citizens on the other (Figure 8). Coupling the tumultuous career path of an honored military veteran, driven by 1963 constitutional changes in SFRY as well as the town-planning cycles in Titograd, the story un-shadows the local streams of power distribution embodied through unostentatious but important advances in local architectural scene. While the old comrades and the socialism are long gone now, the building continues to emanate the integrity of both social and environmental character, acting as a measuring tool for justifiable comparison between the epochs’ achievements.

Figure 9. Diagram made by the author.

Figure 9. Diagram made by the author.

September 2024, Montenegro

Get updates from balkan story map.

Building bio

BUILDING BIO

Name of the building: Beogradska 8/6

Former name of the building/neighborhood: Residential building for executive bodies of the Socialist Republic of Montenegro

Current Address/District: Gorica C District, Beogradska Street 8/6

Period of design: July 25th 1963

Period of construction: 1963/1965

Author/Architect/s/Urban planner: Architect Jovica Milošević (1929‐2013)

Institution/Architectural studio: Design bureau of the Organizational‐construction Company “Titograd” (OGP)

Construction company: Organizational‐construction Company “Titograd” (OGP)

The number of buildings: 1

Number of apartments: 5