Gjakova's journey during the period of industrialization (1960-1990) is a story of profound transformation and growth. Amid this industrial boom, the city's urban landscape began to change, with the construction of the first collective housing complexes. The shift was not confined to the architectural and urbanistic sphere only, because the city's new buildings, whether factories or residential ones, brought along social and economic changes as well. All these developments aligned with Former Yugoslavia's plan to reshape economic and social structures, through industrial projects and urban planning initiatives. However, this rapid wave of modernization was always interacting with the traditional values deeply rooted in the population.

Industrial development began as early as the first half of the 20th century, with the first industrial factory being a tile factory, and the construction of a mill with an electric power plant (Industria, 2015). In the pre-industrial era, the heart of the city was The Grand Bazaar,1 situated near the river Krena, known not only for its economic function but also as the core of social and political life. It was only after the establishment of factories, that the economic and social activities were displaced on the other side of the river (Bakija & Nushi, 2015). After the Second World War, the city's economy began to concentrate on craft cooperatives, such as the cooperatives of shoemakers, tailors, trade cooperatives, and others for municipal services. Later, around the 1960s, it included textile manufacturing, along with food production, like bread, jam, and meat processing (Industria, 2015).

Gjakova’s economic prosperity hit its peak during the 70s when several industries were introduced into the city.2 The textile industry in particular stood out with factories producing yarn, fabrics, knitwear, as well as heavy and light clothing. The metal industry developed alongside with production of pipes, wire products, and enamelled Teflon-coated vessels; electrical engineering with the production of electric motors; the wood processing industry, the rubber industry, the production of technical gases, the tobacco industry, construction and production of building materials (Industria, 2015).

Among the main factories were the fruit-juice processing enterprise "KBI Ereniku", the garment and knitwear enterprise “HC JATEX”, the metal enterprise "KI Metaliku", the textile enterprise "KI Emin Duraku", the construction industry "KN Dukagjini", the commercial enterprise "KT Agimi", the tobacco collection factory "KBI Virgjinia", the electric motor factory "KI Elektromotori", the brick factory “KN IMN”, the public waste-management enterprise "Çabrati", the enterprise specialising in processing doors and windows “Modeli”, the mineral processing factory “Deva”, and the enterprise specialising in the production of bread and other baked goods “Žitopromet”, amongst others.

In 1971, Gjakova had over 20 enterprises and 71.367 inhabitants (Gjakova Portal, 2015) over 20,000 of which were employed in these factories, alongside a diverse number of production experts, including engineers in mechanical, electronic, and electrical fields, as well as professionals in construction, architecture, food technology, chemistry, textiles, and agronomy. Many of these experts were trained in countries like the USA, France, Italy, and Germany, which enabled the usage of advanced Western equipment.

Various products of metallic, textile, or wood in nature, as well as construction materials and rubber products, were exported to countries such as Germany, Italy, Canada, the U.S., Russia, Poland, Greece, Bulgaria, Albania, and the countries of former Yugoslavia, with an export value of around 100 to 120 million dollars annually (Industria, 2015).

The bloom of industry did not come alone; it brought other important changes. The Titoists'3 process of industrialization accelerated Kosovo's urbanisation, expanding, thus, the small towns like Peja and Gjakova, which had earlier developed along Ottoman trade routes (Pettifer, 2002).

Among the people of Gjakova, many decades later, the echoes of the city's industrial awakening still dwell in their conversations — both among those who lived through that period and those who know it through the stories — lingering in the corners of the streets and in the concrete of the collective buildings that first appeared during that time. The landscape of a city once adorned with houses began to alter, for residential buildings emerged as the first touch-ups of modernity, against the background of the old.

With its concrete façade and asymmetry, the new buildings were a bold departure from the town’s traditional aesthetic, but one that complied perfectly with the modernist style in architecture, brutalism (Giuroiu, 2024). Although brutalism was very prominent in Europe, after World War II, Former Yugoslavia seemed to have adapted it as a means to establish a distinctive visual identity, a socialist utopia, while caught between democratic West and communist East (The Guardian, 2019). Following World War II, Kosovo, under Yugoslavian rule, underwent numerous cycles of development, in search of progress and modernization. As a result of the industrial boom and the establishment of factories, the number of inhabitants in the cities increased, causing a drastic transformation in architecture, public buildings, tourist sites, and social life (Beqiri, 2020).

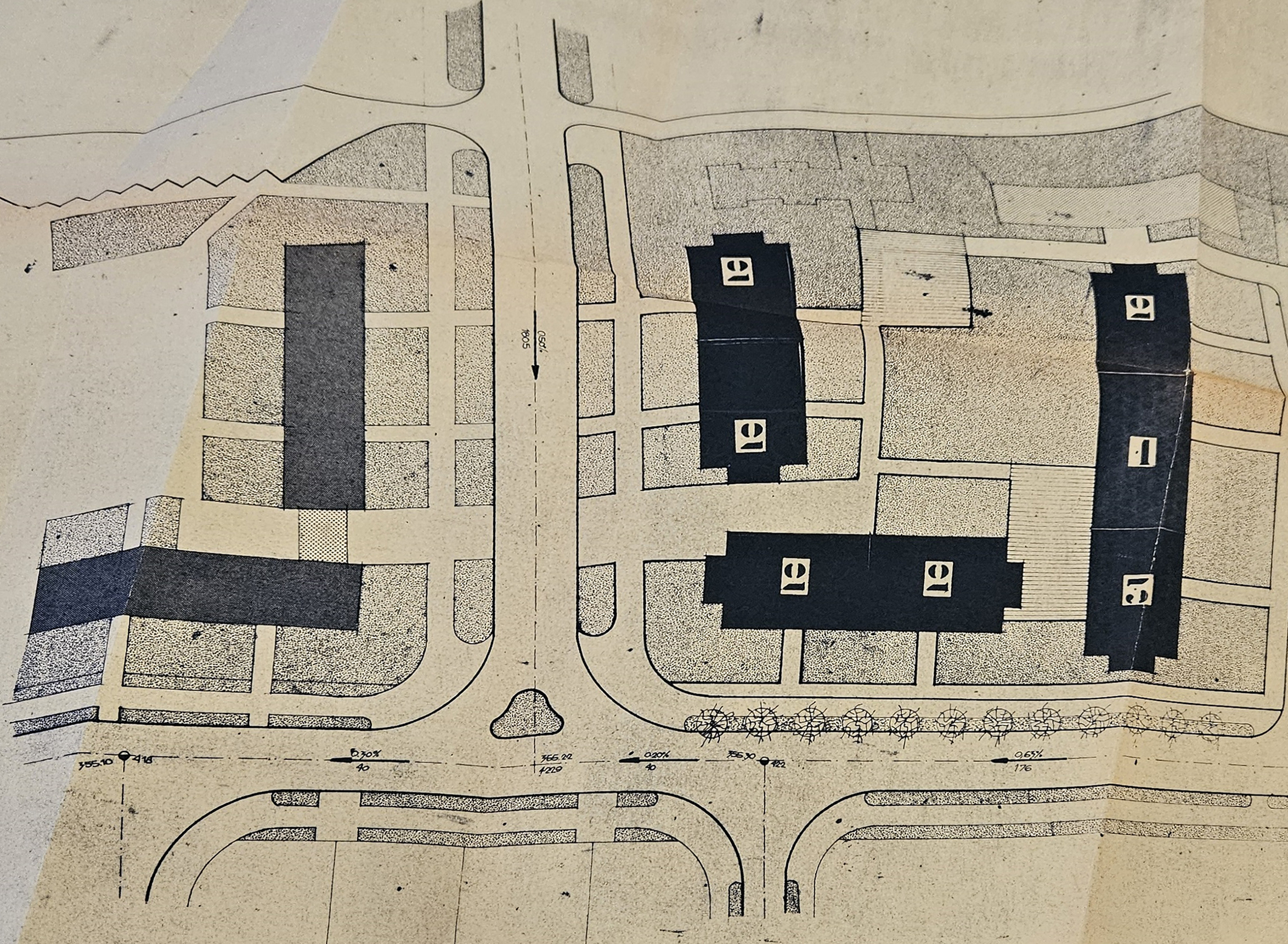

Among the earliest collective buildings that transformed the scenery of the city, are the ones designed by architect Miodrag Pečić4 in 1976, an architect who worked at the Institute for Urbanism and Project Planning of Prishtina. Very active during that period, Pečić designed several buildings across the country, including the Institute of Albanology (1974-1977), the Neuropsychiatry building (1979), and the building of Gynecology (1974), all of the abovementioned located in Prishtina (Sadiki, 2020). Moreover, he designed the set of residential buildings in Gjakova (Figure 1), funded by the enterprise “Dukagjini.” This complex is known locally as Banesat Kineze or Banesat e Solidaritetit.5

Figure 1. Position of the buildings within the neighbourhood. Retrieved in 2024 from the City of Gjakova Archives.

Figure 1. Position of the buildings within the neighbourhood. Retrieved in 2024 from the City of Gjakova Archives.

Located between the streets Yll Morina, St. Anton Çerta, and St. Migjeni, these mass collective buildings have been part of the city’s landscape since the 70s, with a very unique structure that set them apart from other multi-family apartment buildings in the town (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Residential Building , Gjakovë (1976), designed by architect Miodrag Pečić (Gjinolli & Kabashi, 2015, p. 34)

Figure 2. Residential Building , Gjakovë (1976), designed by architect Miodrag Pečić (Gjinolli & Kabashi, 2015, p. 34)

Although today much of the building’s façade is covered by trees, one can still distinguish the concrete shapes, bold and unadorned, as it was originally envisioned when it was designed (Figure 3). The architectural elements between the balconies were likely designed not solely for their visual appeal but to ensure privacy between units. As Agon Qela, a local architect, observes, during that era, "aesthetics primarily emerged from functionality."

Figure 3. Current condition of Banesat Kineze Complex. Photography taken by the author in 2024

Figure 3. Current condition of Banesat Kineze Complex. Photography taken by the author in 2024

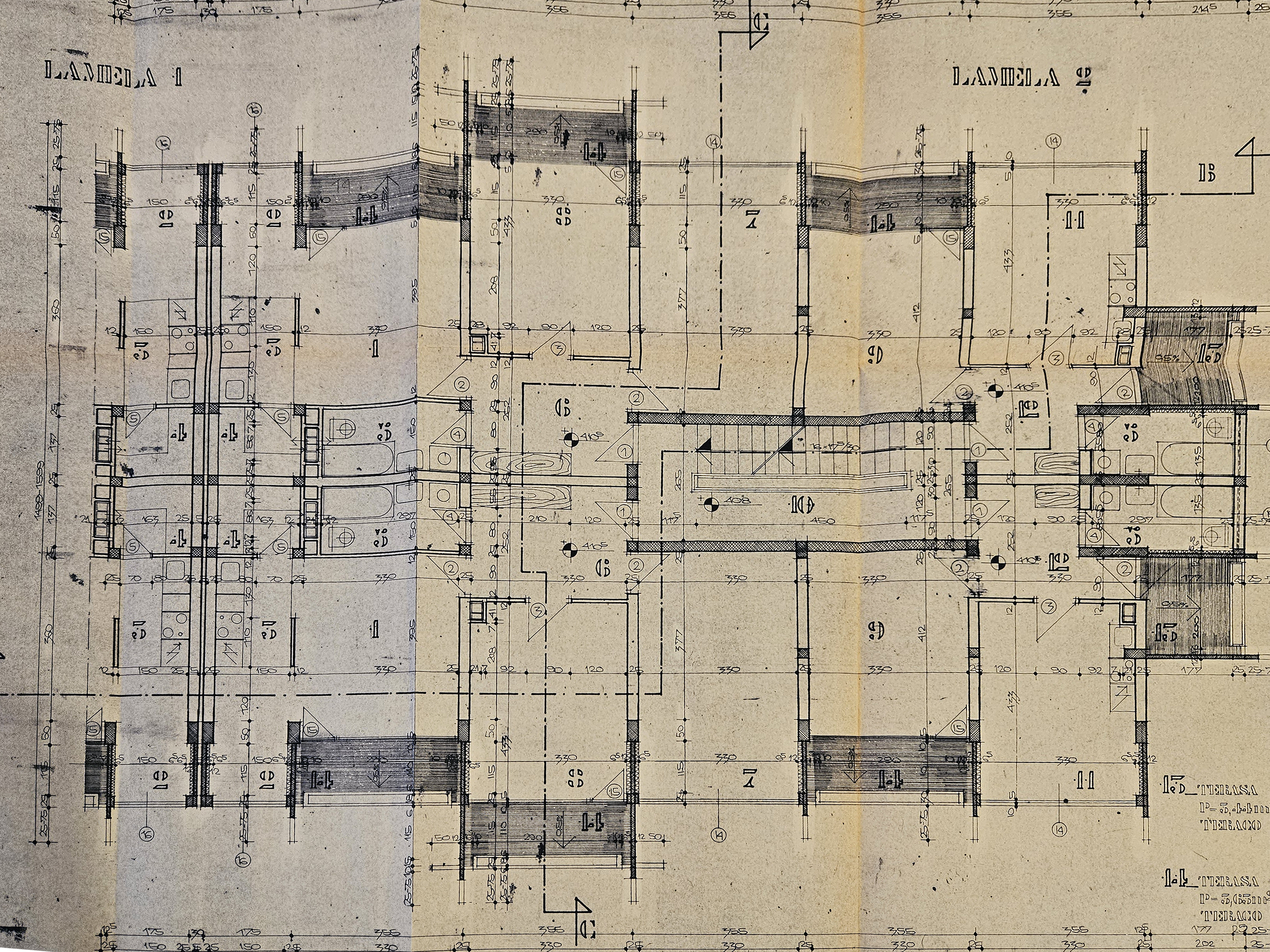

The residential building features one- and two-bedroom apartment typologies, as outlined in the blueprint. The two-bedroom apartments include a combined living room and kitchen area, a bathroom, two balconies, and a small storage room. Both apartment types are systematically arranged with four units per floor within a five-story building (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Blueprint of the floor plan from the original project (Projekti Kryesor Blloku banesor "Orize" Lamela 2), Gjakova, 1976 by architect Miodrag Pecic. Retrieved in 2024 from the city archives.

Figure 4. Blueprint of the floor plan from the original project (Projekti Kryesor Blloku banesor "Orize" Lamela 2), Gjakova, 1976 by architect Miodrag Pecic. Retrieved in 2024 from the city archives.

Though initially, the apartments appear to meet the essential living needs, during the interview with a couple that lives in one of the apartments, it was hinted that additional elements, such as a second bathroom, would make the space more accommodating. Despite a quiet desire for more space and convenience, the owners of these humble apartments had frequent friends and family gatherings. When asked if the apartments were spacious enough for such gatherings, the couple simply smiled. The question of space seemed almost irrelevant, an afterthought as if it had never crossed their minds. “Our family and friends are always welcome here,” they said. It is almost as if space seemed to stretch and bend, to accommodate not only the visitors but also a cultural identity that wasn’t tied down to space; it transcended it.

Generally speaking, different societies often have unique ways of perceiving and interacting with space, and this relationship between space and culture has always been a delicate matter in the Albanian tradition as well. Throw the economic conditions in the mix, and families sharing a communal space was the norm; before the rise of modern flats, brothers, each with their own families, lived together under one roof. Mass collective buildings introduced a very new concept into the lives of the couple: privacy. The transition was not just architectural but also social, in which communal bonds adapted and were manifested in new forms.

There are a few aspects that differentiate Yugoslavia’s mass housing from other socialist countries; the main one being that the housing surge was fuelled by competitive self-managed construction firms targeting institutions in need of employee housing, so they were not state-owned property; it was “social property” (McGuirk, 2018). Similarly, while in need of an enormous workforce, some of the factories that were established during the industrial boom in Gjakova at that time bought the apartments and leased them to their workers, for what the workers themselves called “a small rental fee”.

Çabrati, the public waste-management enterprise, is among the factories that purchased apartments in the abovementioned complex, Banesat Kineze, for their workers. However, the distribution of these units was not decided by the factory itself. According to an interviewed employee of the enterprise, who also owns one of the flats, it was the workers' council that oversaw the distribution process.6

Members of this council were elected by the general workforce to represent them in important decisions such as this. During their meetings, they discussed and voted on who would receive the apartments. They followed this system in which financial circumstances, work experience, dedication to their job, and similar factors were considered as crucial criteria for a worker to obtain an apartment.

As the same interviewed workers reported, a percentage was deducted from all workers’ salaries to finance the housing. However, not all workers benefited from this, because not all of them were able to obtain an apartment. Priority for housing was given to leaders and then came the rest of the employees, particularly those who were married. This system resulted in some workers contributing to the obligatory housing fund without ever receiving an apartment.

During interviews with both recipients and non-recipients of the flats, they seem to recall a strong interest of people back then in obtaining individual loans to build personal houses instead of accepting the flats; an underlying connection that linked housing choices with social status. There was a belief that owning your own home, as opposed to living in mass-produced flats, was a marker of higher social standing. The walls of mass-produced flats, though sheltering, held the symbol of necessity rather than comfort. Architecture, in this sense, always performs as a symbol of status in society. It appears that, even if it went unnoticed, as a sort of instinct, people have always associated space with something profound and meaningful. Amidst these conversations, it was also revealed that even though there were a lot of workers from villages or outskirts of the city that were employed in these factories, some preferred to live back home, in their own spacious houses, surrounded by gardens, negating, thus, the assumption that urbanisation is inherently desirable or beneficial for all. Many of them found comfort and identity in their own homes, something that urban living cannot easily replicate.

The rapid establishment of various factories, in the mid-20th century, transformed Gjakova into an industrial centre. The construction of collective housing complexes like the Banesat Kineze, designed by Miodrag Pečić, played an essential role in the urban transformation of Gjakova. These buildings were not just physical structures but symbols of a broader social experiment aiming to create a new, modernist identity within the city. The shift from traditional “mëhalla” neighbourhoods to these modern flats was intended to promote a sense of equality and communal living. Thus, the sentiment for this period is complex, because, while it brought economic prosperity and urban development, the benefits were not equally distributed. While these apartments were initially envisioned as a means to improve living standards and provide housing to workers, the reality often fell short of the ideal. Many workers, who were long-term contributors to the housing funds, never received the promised housing.

A lingering nostalgia for that era persists among those who lived through it, even though the conditions they face today remain as challenging as they were then. The transformation from a nascent urban area into a fully developed township was indeed a significant leap, one that is difficult to forget. However, the utopian aspirations of that time were never fully realised. What remains of that development is now deteriorating, and the promise of progress has failed to materialise for many, much as it did in the past.

The architectural shift to socialist modernism, characterised by its stark, utilitarian forms, symbolised the state's commitment to equality, collective progress, and the rejection of bourgeois excess. However, its impact was largely confined to urban areas. While these developments aimed to promote efficiency and unity, the socialist utopian ideal remained largely theoretical. It accommodated only a select group integrated into the new social order while failing to convince or include the majority.

It would seem that it couldn't have spread further than the concrete walls of the modernist flats.

September 2024, Kosova

Get updates from balkan story map.

Building bio

BUILDING BIO

Name of the building: Banesat Kineze or Banesat e Solidaritetit

Former name of the building/neighborhood:N/A

Current Address/District: Located between the streets Yll Morina, St. Anton Çerta, and St. Migjeni

Period of design: 1976

Period of construction: 1976-1978

Author/Architect/s/Urban planner: Miodrag Pečić

Institution/Architectural studio: Enti per Urbanizem dhe Projektime (Eng. Institute for Urbanism and Project Planning)

Construction company: Enterprise “Dukagjini”

The number of buildings:2

Number of apartments: Four units per floor, in a 5-story building.