Unfortunately, never before in history

has it been so clear that the destruction

of a city is the destruction of life.

(Buden & Pavićević, 2020, p.26)

What is space? Who owns space? Architect Novak Jovović,1 82, offers a profound perspective on this concept - "Space is the basis for life, and it belongs to all people. If we take this into account, we will recognize the need for the use of space, which, by the nature of both space and human life, belongs to everyone. Space should be defined collectively by the people who wish to use it. It cannot be exclusively defined by the current owner of that space." (Vijesti, 2020).

A reflection of his philosophy to feeling and shaping space2 can be seen at the end of Mediteranska Street in Budva, where the Avala S553 building aligns with the contours of the hills on both sides of the coast. Although it now contends with the construction boom that threatens to engulf it from all sides, few residents of Budva and tenants of the building know that it won the “Borba” architecture award at the republic level for Montenegro in 1972. Jovović’s design was recognized by the jury as a remarkable achievement in the field of residential architecture in Montenegro, noting how the project skillfully united functional solutions with artistic expression4 (Alihodžić, 2015, p. 61).

Figure 1. Avala Building S55, Mediteranska Street, Budva, 1972, arch. Novak Jovovich. Retrieved from Facebook group Budvanostalgičari.

Figure 1. Avala Building S55, Mediteranska Street, Budva, 1972, arch. Novak Jovovich. Retrieved from Facebook group Budvanostalgičari.

In today’s Budva, where rapid construction resembles a chaotic game of Tetris, the Avala S55 building stands out. Its design and the residents' experiences reflect a more thoughtful approach to human well-being and quality of life.

Avala S55 was built and occupied in just six and a half months, which, as Jovović points out, was an absolute record. The goal was to quickly house the workers of the Avala Hotel company. As noted in the "Primorske Novine" in February 1972, the “Beauty” caused a stir among the workers—four times more employees were interested in these comfortable apartments than the number available (Radulović, 1973).

In the 60s, before the construction of the building, “from the small P+4 solitaires towards Avala, on the right side, there were no structures at all leading up to Budva,” recalls Jovović. That part of Budva was swampy, as indicated by its old name, Velja Voda, and by the childhood memories of the building’s residents. One resident5 remembers how he and his friends would play in the reeds and get punished by their parents for coming home covered in mud. The old Budva locals, who owned livestock, would bring their animals to drink at Velja Voda. To combat the swampy terrain, eucalyptus trees were planted throughout the area due to their high transpiration rate, which helped to dry out the land.

Figure 2. Photograph of Budva, 1950. Retrieved from Facebook group Budvanostalgičari.

Figure 2. Photograph of Budva, 1950. Retrieved from Facebook group Budvanostalgičari.

The ground in that area had very poor load-bearing capacity, making it unsuitable for construction, according to the old residents of Budva. The land needed preparation to support the building, says Jovović. They performed a soil replacement, preceded by a soil examination conducted by the Institute for Material Testing of Serbia. They removed the existing soil layers and brought in crushed stone, which they compacted, thus performing the soil replacement mechanically, he explains.6

The building consists of three sections, with floors ranging from P+3 to P+4. It includes studios, one-bedroom, two-bedroom, and three-bedroom apartments, with sizes ranging as follows: 16-18 m², 45-47 m², 68-70 m², and 76-78 m². Two-bedroom apartments, designed for four-member families, are the most common and include a living room, kitchen, dining area, two bedrooms, and a bathroom. The bedrooms share terraces, allowing natural light, ventilation, and airflow from both sides of the apartment. The units are dual-oriented, offering more natural light and opportunities for natural ventilation. In the summer, the living area can be expanded by using the terrace, and the kitchen and dining area can be opened up for seasonal use.

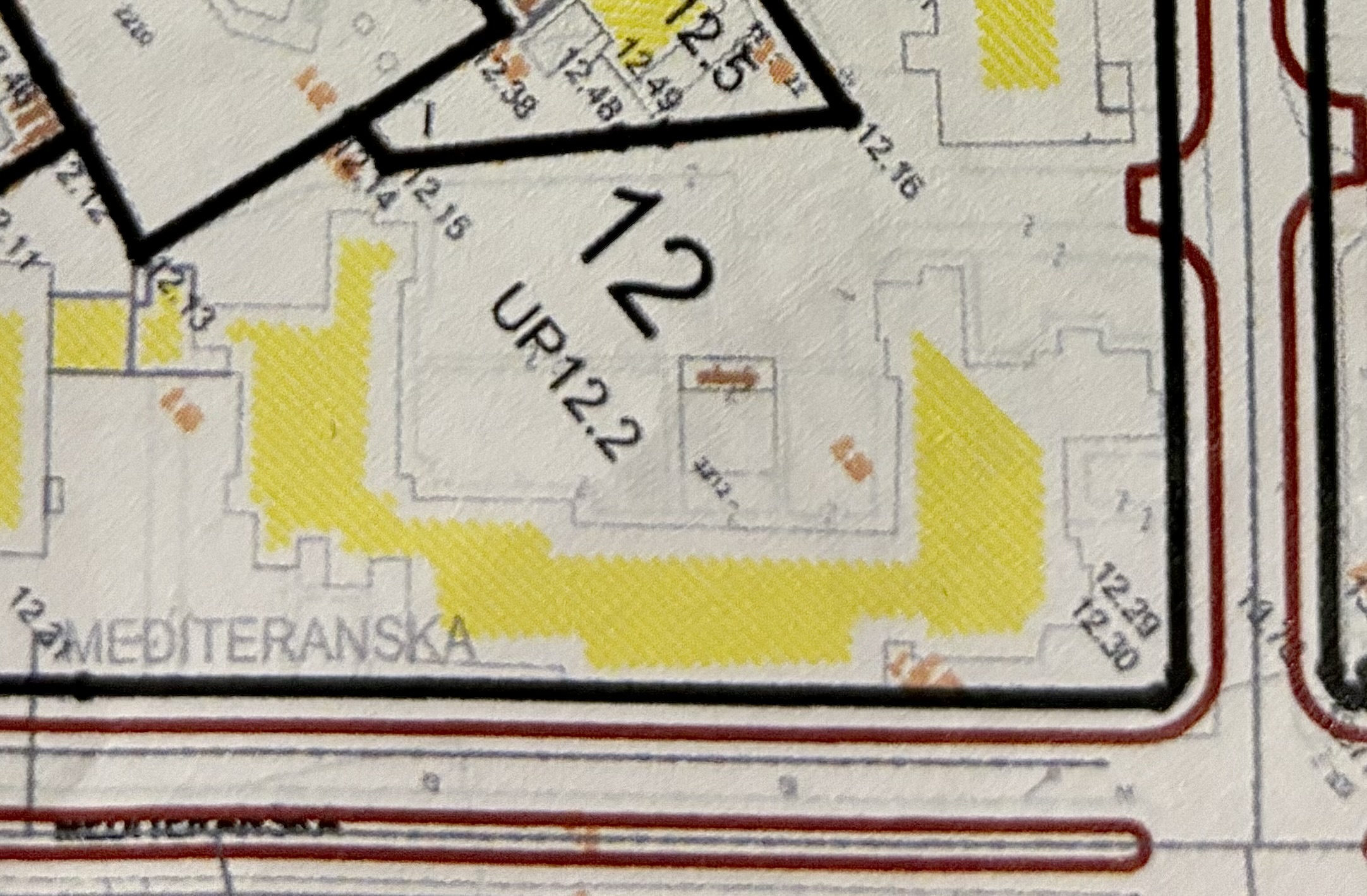

Figure 3. Avala S55 building in the current planning documentation, retrieved from Municipality of Budva.

Figure 3. Avala S55 building in the current planning documentation, retrieved from Municipality of Budva.

The Avala S55 building was constructed using a honeycomb structural system, characterized by uniform vertical and horizontal elements.7 Jovović, who was present during the 1979 earthquake, provides a testament to the robustness of this design: “At 07:19, I was in front of the building after buying bread, while my family remained inside the apartment. The building sustained no damage, and even the facade cladding remained unaffected. Only the expansion joints activated, functioning as intended during seismic activity.”

The residents express confidence in the building’s safety concerning potential seismic activity. During the 1979 earthquake, their neighbor, Jovović—known affectionately as Mili—assured them that returning to the building was the safest option, as it provided superior protection.

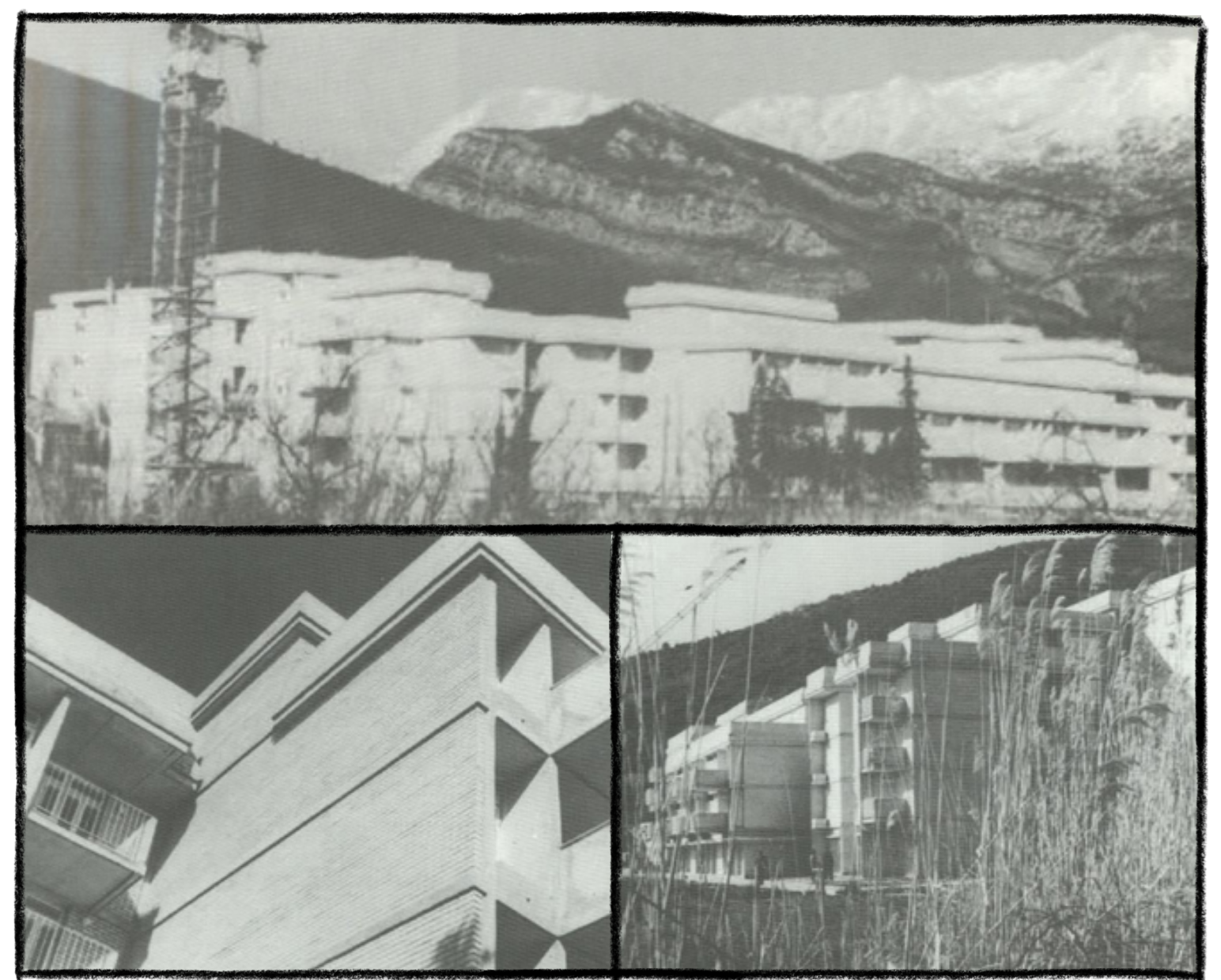

Figure 4. Collage of photographs of the Avala S55, retrieved from Alihodžić (2015).

Figure 4. Collage of photographs of the Avala S55, retrieved from Alihodžić (2015).

Beyond ensuring the safety of the residents, Jovović also considered the impact of spatial design on mental well-being. He believes that when basic design standards and regulations are poorly interpreted, leading to weak technical and spatial solutions, these apartments negatively influence personality development. Such environments can foster poor mental states and deviant expectations in family or neighborly relations, the architect asserts. He emphasizes that the goals of planning and design are crucial, as they ensure the healthy reproduction of society.

The astonishing acceleration of life’s pace in the last century

has compressed time into a flat curtain of the present,

onto which the simultaneity of the world is projected.

As time loses its continuity and its resonance with a justified past,

individuals cease to perceive themselves as historical beings

and face the threat of a "fear of time".

(Pallasmaa, 2012, p. 59-69)

You will recognize the Avala S55 building by its over 50-year-old Temerin brick,8 in a light terracotta color that still withstands the test of time and stands as a Sun amid the anti-Mediterranean architecture of this part of the city. Though slightly weathered, the brick has retained its original color since the facade was installed, eliminating the need for renovation. Despite the sunlit facade, the reality today, after 53 years and the urban decay in Budva, reveals dark entrance halls marked by graffiti, old political flyers, and empty apartments where only beams of light are visible through peepholes. Few cautious residents open their doors to briefly discuss life in the building.

Figure 5. Avala S55. Photography taken by the author in 2024.

Figure 5. Avala S55. Photography taken by the author in 2024.

Some balconies have been glazed over time and repurposed as additional rooms. Jovović recalls that one resident wanted to enclose his rooftop9 balcony with glass, resembling a greenhouse (Figure 6, left), and this intervention still exists on the last section of the building, as viewed from the Old Town. Additionally, one family "extended" their apartment by shortening the corridor within the building (Figure 6, right), and over time, more apartments were built by some residents on the top floors of the building. Although architect Jovović, as the author and someone who should have priority in such decisions, did not support these modifications, residents continued to alter their living spaces to suit their needs.

Figure 6. Modifications to the building: collage of Avala S55, past and present (left); corridor within the building (right). Photograph taken by the author, 2024.

Figure 6. Modifications to the building: collage of Avala S55, past and present (left); corridor within the building (right). Photograph taken by the author, 2024.

In some apartments, the original plastic chandeliers have endured, costing between 1,000 and 2,000 dinars, as mentioned in Primorske novine (Radulović, 1973). Residents recall that the apartments came with kitchen hoods from the start. The carpeting in the living and bedrooms, along with the white "DIN Novoselec" woodwork from Croatia, has also lasted over the years. Workers from the woodwork factory would visit, take measurements, and handle the installations, while Jovović sketched the details—even visiting their factory to ensure everything was crafted according to his design. A long-standing shop on the building’s ground floor, the tailor shop "RADE," has remained unchanged for decades and is a familiar name throughout the city.

The quality of life in the Avala S55 building shifted when investors began taking over the land around it, gradually eroding the material and spiritual aspects of life that residents had once enjoyed within the building and its surroundings.

There’s noise, passersby... they’ve blocked our sunlight with high-rises!” one resident said angrily. A significant number of the original families who lived in the building have sold their apartments, but, according to one resident, they say they could not find such quality living conditions elsewhere. Today,10 when knocking on residents' doors, most of the apartments give no sign of life. Although many units are vacant, some are rented out during the tourist season to seasonal workers, or year-round to Russians and Ukrainians.

Figure 7. In the center of the photograph, the Avala S55 building between new buildings that block the sunlight. Photography taken by the author in 2024.

Figure 7. In the center of the photograph, the Avala S55 building between new buildings that block the sunlight. Photography taken by the author in 2024.

As if the elitist glass Porto cities were not enough, the construction of the future "Porto Budva" is now underway near the Avala building. It is part of a series of buildings obstructing the Avala residents' view of the sea and the hilly landscape that frames the scenery. What was once a parking lot, and before that, a reed-filled area with a beautiful rocky shoreline, is now overshadowed. One resident claims that for nearly 50 years, he enjoyed eating watermelon on his balcony during the summer, but now, due to the noise from nearby construction sites, he can’t even hear his wife sitting just a meter away from him.

Figure 8. Balconies of Avala S55. Photography taken by the author in 2024.

Figure 8. Balconies of Avala S55. Photography taken by the author in 2024.

"Is architecture something we build for ourselves, or should it also remain for those who come after us?" Can what remains, limit those to whom we leave it?” These were questions Jovović contemplated throughout his prolific career, reflecting on the dimension of time.

Such visionary thinking is rare today, as most of the newly constructed glass buildings around Avala S55 in Budva appear cold and only deepen the sense of human alienation. It is natural for people to be surrounded by materials that embody the passage of time. Daily exposure to natural processes—like the gentle aging of brick, the wear on parquet, the appearance of a new bud in a planter below a window, or a newly lived memory—enriches our experience. With proper maintenance, these elements help us recognize the beauty in the passage of time and in what we leave behind.

Figure 9. Inscriptions on the brick at the building entrance, over 40 years old. Sourced from the Facebook group Budvanostalgičari.

Figure 9. Inscriptions on the brick at the building entrance, over 40 years old. Sourced from the Facebook group Budvanostalgičari.

Over two centuries ago, Du Mare11 analyzed human alienation as reflected in language, noting the increasing use of nouns representing possessions, as opposed to the earlier dominance of verbs and processes (Fromm, 1976). What was once expressed as “I live in an apartment” has now, under the constraints of capitalism, become “I own an apartment.” It seems that the residents of the Avala S55 building are among the few in Budva who have the privilege of preserving the memory of living in their apartment.

September 2024, Montenegro

Get updates from balkan story map.

Building bio

BUILDING BIO

Name of the building: Avala building/Building of Avala

Former name of the building/neighborhood: Avala S55

Current Address/District: Mediterranean street, Budva (formerly known as Velja voda)

Period of design: 1970

Period of construction: 1970-1971

Author/Architect/s/Urban planner: Novak Jovović

Institution/Architectural studio: Avala hospitality/Avala engineering

Construction company: Novotehna, Novi Sad

The number of buildings: 1 building, 3 wings (sections)

Number of apartments: 55 apartments

Types of dwelling units: Studio apartments, one bedroom, two-bedroom, three-bedroom apartments; 18m2, 47m2, 70m2, 78m2