In the post-World War II period, Prishtina, like many other cities within the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, underwent profound transformations that redefined its urban fabric and societal structure (Simić, 1974). These changes were evident in shifts in spatial organisation, land use, and population distribution as the city transitioned from traditional patterns to a modernist urban environment (Figure 1). Central to this transformation were the introduction of systematic urban planning and the widespread construction of multifamily residential blocks. Emerging in Prishtina during this period, these residential buildings marked a significant departure from the city’s traditional urban fabric, embodying broader regional and global trends in urbanisation.

Figure 1. Historical development of Prishtina’s urban area. Retrieved from the Strategic development plan of Municipality of Prishtina, 2004.The shift towards multi-apartment residential buildings as the dominant housing typology in Prishtina did not occur in isolation (Hirt, 2013). It was part of a broader socio-spatial transformation that swept across the Yugoslav Federation and beyond. This shift, primarily driven by the imperatives of rapid industrialization, can be interpreted as a form of modernization within a broader context, closely intertwined with Prishtina's evolving political status within the Yugoslav Federation. By the mid-20th century, as the capital of the Autonomous Province of Kosovo and Metohija,1 Prishtina’s significance was progressively elevated through key constitutional changes, most notably the 1974 Constitution, which granted Kosovo greater autonomy within Yugoslavia. This enhanced political status facilitated increased investment in Prishtina’s urban infrastructure, further accelerating its urbanisation and transformation (Sadiki, 2020).

Figure 1. Historical development of Prishtina’s urban area. Retrieved from the Strategic development plan of Municipality of Prishtina, 2004.The shift towards multi-apartment residential buildings as the dominant housing typology in Prishtina did not occur in isolation (Hirt, 2013). It was part of a broader socio-spatial transformation that swept across the Yugoslav Federation and beyond. This shift, primarily driven by the imperatives of rapid industrialization, can be interpreted as a form of modernization within a broader context, closely intertwined with Prishtina's evolving political status within the Yugoslav Federation. By the mid-20th century, as the capital of the Autonomous Province of Kosovo and Metohija,1 Prishtina’s significance was progressively elevated through key constitutional changes, most notably the 1974 Constitution, which granted Kosovo greater autonomy within Yugoslavia. This enhanced political status facilitated increased investment in Prishtina’s urban infrastructure, further accelerating its urbanisation and transformation (Sadiki, 2020).

The year 1953 marks a pivotal moment in Prishtina's urban development, symbolising the beginnings of structured urban planning in the city. It was during this year that the Urban General Plan for Prishtina (1950-1980) was adopted, and drafted under the leadership of Belgrade architect Dragutin Partonić2 by the Iskra planning group3 (Jerliu, 2023). This plan is widely recognized as Prishtina’s first comprehensive urban strategy, laying the groundwork for the city's transformation and its anticipated population growth. The plan anticipated a substantial population increase, projecting nearly a doubling in size. By 1971, the population had indeed risen to 69,524, reflecting the rapid urban expansion that defined this era (Sadiki, 2020). The most notable aspect of the plan was the introduction of neighbourhood blocks of multi-residential apartments, marking a departure from traditional urban forms and setting the foundation for Prishtina's modern architectural landscape.

Figure 2. Snap from Urban General Plan for Prishtina (1950-1980). Retrieved from the Municipality of Prishtina Archives.

Figure 2. Snap from Urban General Plan for Prishtina (1950-1980). Retrieved from the Municipality of Prishtina Archives.

A decade later, the "Program for the Urban Design of Three Residential Neighbourhoods and the Center of the New Part of the City" was developed under the guidance of Bashkim Fehmiu,4 who played a pivotal role in shaping Prishtina’s evolving urban environment. This program further emphasised the transition towards multifamily residential buildings, reflecting broader regional and global urban development trends (Kerkezi, 2018). The plan projected that only 15% of residents would live in single-family houses, while the majority, 60%, would reside in four-story multi-apartment buildings. An additional 15% were expected to live in five-story (P+4) residential buildings, with the remaining 10% allocated to solitaire typologies exceeding ten floors. This represented a clear shift away from Prishtina’s prewar urban fabric and underscored the city’s move towards a denser, more urbanised form (Sadiki, 2020).

Within this urban development program, the neighbourhood of Ulpiana was envisioned as a key component of Prishtina's growth. The planning and construction of Ulpiana in the 1960s and 1970s exemplified modernist urban principles and served as a model for the city’s evolution, reflecting broader trends in 20th-century urban planning (Sadiki, 2020).

The Ulpiana neighbourhood located in the southern part of Prishtina and completed in 1968, is a prime example of modernist urban planning from the latter half of the twentieth century. The neighbourhood showcases an example of a carefully planned grid and spatial organisation, which prioritise systematic layout and functionality (Figure 3). Inspired by the principles of modernist design from the 19th century, Ulpiana’s layout features the regulation of buildings within patterned streets and uniform geometric shapes. Moreover, Ulpiana reflects the movement’s key ideas of simplicity and minimalism. The neighbourhood’s design avoids ornamentation, focusing instead on clean lines, practical spaces, and a cohesive layout intended to create an efficient urban environment. This approach follows the modernist belief that "less is more," emphasising utility and efficiency in both urban planning and architecture (Hickel, 2021).

Figure 3. Snap of Ulpiana neighbourhood from Urban General Plan for Prishtina (1950-1980). Retrieved from the Municipality of Prishtina Archives.

Figure 3. Snap of Ulpiana neighbourhood from Urban General Plan for Prishtina (1950-1980). Retrieved from the Municipality of Prishtina Archives.

Ulpliana’s residential façades adhere strictly to modernist principles, intentionally avoiding decorative elements. This absence emphasises the functionality of the architecture, highlighting its practical and efficient design. Horizontal and vertical lines—seen in the alignment of windows, balconies, and structural elements—introduce a rhythmic quality to the visual composition. The neighbourhood itself is thoughtfully composed, with curved and rectilinear blocks that harmonise with the natural contours of the landscape. Positioned on a hill, the four solitaire buildings serve as focal points, accentuating the stepped topography and anchoring the district visually (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Photographs of the research site taken by Donika Çapriqi, 2024.

Figure 4. Photographs of the research site taken by Donika Çapriqi, 2024.

These four towers, organised around a central circular fountain, serve as both architectural and urban landmarks. The Solitaires embody the essence of modernist architecture, with their minimalist design and functional form. The unadorned facades and clean lines of these buildings are a direct manifestation of the modernist principle articulated by Adolf Loos that "Ornament is Crime," emphasising utility and simplicity over decorative excess (Loos & Masheck, 2019). Beyond their architectural significance, the Solitaires are also a well-known reference point for Prishtina residents, marking one of the city’s most recognizable locations (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Ulpiana’s Solitaires, with “the fountain at the centre”. Photographs retrieved from public Instagram account prishtinaheatsave project of Termokos.

Figure 5. Ulpiana’s Solitaires, with “the fountain at the centre”. Photographs retrieved from public Instagram account prishtinaheatsave project of Termokos.

Inside the buildings, the apartment layouts epitomise modernist residential architecture, emphasising functionality, efficiency, and utilitarian principles. Utilising a 60 cm grid system, the design adopts a modular approach, enabling rapid, cost-effective construction while ensuring uniformity across units (Figure 6). This modularity is evident in the repetitive arrangement of apartments, which features distinct zoning of private (sleeping) and public (living) spaces. Reflecting Le Corbusier's notion that "a house is a machine for living in"5 these designs prioritise practical, standardised living environments over individualistic or luxurious elements, aligning with the era’s focus on utilitarianism (Le Corbusier, 1963).

Figure 6. Snaps of selected Ulpiana building plans, showcasing the layouts of their apartments. Retrieved from the architecture students at UP generation (2015-16).

Figure 6. Snaps of selected Ulpiana building plans, showcasing the layouts of their apartments. Retrieved from the architecture students at UP generation (2015-16).

One of the defining features of Ulpiana’s urban plan is the deliberate and substantial inclusion of public, recreational, and green spaces (Figure 7). These areas were not merely supplementary; they were central to the neighbourhood’s design and stand in stark contrast to the neighbourhoods developed in Prishtina during the post-war, post-socialist era. Unlike these newer areas, where market-driven priorities and privatised land ownership often led to a scarcity of public amenities, Ulpiana was shaped by a vision that prioritised community well-being. The neighbourhood's carefully planned spaces between buildings reflect a deep commitment to fostering social interaction and communal life, elements often missing in more profit-oriented developments.

This extensive inclusion of public spaces was largely a product of Yugoslavia’s state-owned land policies. With land controlled by the state, planners like Bashkim Fehmiu had the flexibility to design a neighbourhood that integrated green areas, recreational zones, and multifunctional spaces into the urban fabric, ensuring that the area supported not just living, but thriving. This approach highlights the positive aspects of centralised planning and land policies focused on the shared good, demonstrating that urban environments can be both functional and socially enriching.

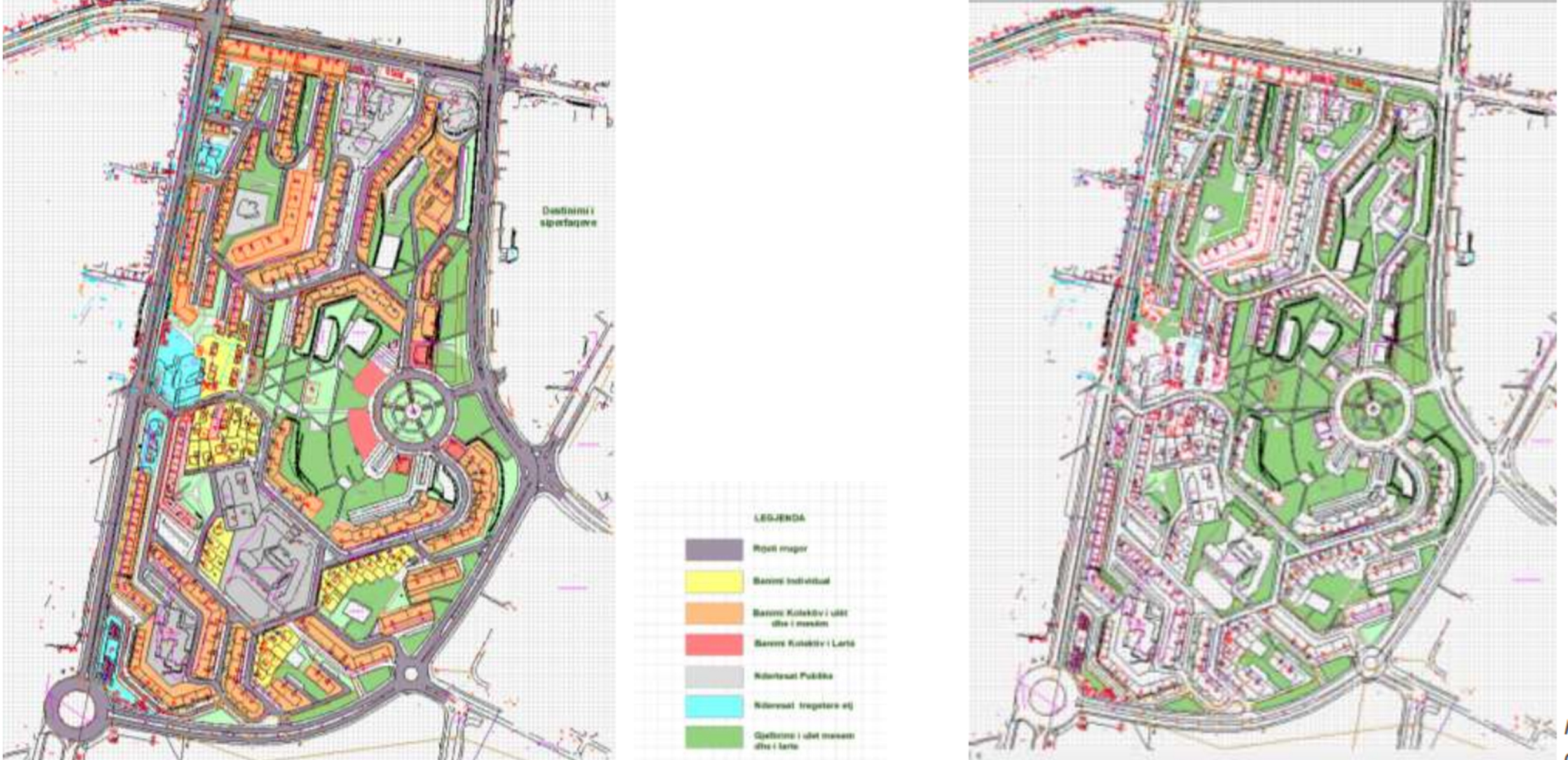

Figure 7. Snap of Ulpiana land use plan (left) and Ulpiana greenery plan (right). Retrieved from the architecture students at UP generation (2015-16).

Figure 7. Snap of Ulpiana land use plan (left) and Ulpiana greenery plan (right). Retrieved from the architecture students at UP generation (2015-16).

In contrast, the shift to privatised land ownership in post-war Prishtina led to a development model that often sacrificed these public amenities. As land became a commodity, the focus shifted toward maximising profits, resulting in denser, more commercially driven neighbourhoods with fewer green and recreational spaces. Ulpiana remains distinctive for its extensive public areas—a lasting legacy of its state-planned origins and the foresight of its planners who understood the importance of creating spaces that serve the community as a whole.

Today, Ulpiana continues to be one of the most livable neighbourhoods in Prishtina, a result of the thoughtful and visionary planning that prioritised public space and communal life (Weber, 2002). Bashkim Fehmiu’s leadership ensured that the spaces between buildings were given as much importance as the buildings themselves, fostering an environment where quality of life is sustained by well-designed public amenities. Ulpiana’s enduring success highlights how urban planning, when guided by principles of the shared good, can create vibrant, inclusive, and sustainable communities.

While the centralised, top-down nature of socialist planning is far from ideal, the success of Ulpiana underscores the positive outcomes that can result when the creation of public spaces is prioritised. The lessons from Ulpiana’s design remind us that housing policies and neighbourhood planning must go beyond merely providing shelter; they must create environments that encourage community, inclusivity, livability, social interaction, health, and opportunities for diverse activities. As we reflect on the legacy of socialist urbanism, it is crucial to acknowledge that its focus on communal spaces offers valuable insights for contemporary urban development, particularly in an era where profit-driven models often overlook the social dimensions of urban life.

September 2024, Kosovo

Get updates from balkan story map.