Ortakoll, the first planned neighbourhood in Prizren, stands out distinctly from other areas. Built in the northwest part of the city in the 80s, it remains one of the few neighbourhoods in Prizren that in addition to housing, it includes amenities such as recreational spaces for sports and socialising, playgrounds, green spaces, parking for the residents, a nursery, an elementary school, a medical centre, and an atomic shelter. This deliberate and structured approach to planning stands in contrast to the older neighbourhoods of Ottoman heritage in Prizren, as well as the newer ones packed with informal buildings.

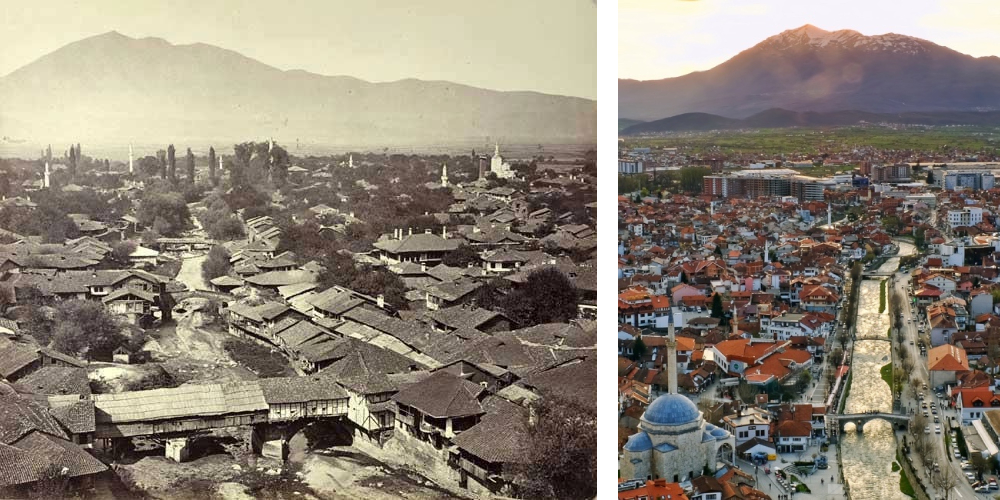

Prizren is renowned as the historical city of Kosovo. For most of its history, the architecture mirrored that of Ottoman cities, with narrow roads and numerous religious Islamic buildings. Downhill from the fortress, cobbled streets lined with traditional houses, extend throughout the city.

Figure 1. On the left: Prizren in 1860, as published in Ceko & Xhibo (2019), retrieved from QRTK Prizren (Regional Center for Cultural Heritage) archive in 2024. On the right: Prizren in 2022, retrieved from Western Balkans Investment Framework website.

Figure 1. On the left: Prizren in 1860, as published in Ceko & Xhibo (2019), retrieved from QRTK Prizren (Regional Center for Cultural Heritage) archive in 2024. On the right: Prizren in 2022, retrieved from Western Balkans Investment Framework website.

As part of the Ottoman Empire, Prizren was the most important city in the province of Kosovo during the 19th century, exhibiting a lifestyle and cultural activities reminiscent of Anatolian cities (Ceko & Xhibo, 2019). The city’s population grew from 12,800 inhabitants in 1623 to 20,000 in the 1830s and 1840s (Riza, 2011).

The old houses in Prizren blend function and purpose, situated in plots of irregular form, they reach a high degree of free composition.1 The gardens, walled and located at the back of the houses, ensure privacy from the street. The ground floors feature thick walls made of sun-dried bricks or stone, while the upper floors were constructed with lighter materials (Fehmiu, 1971).

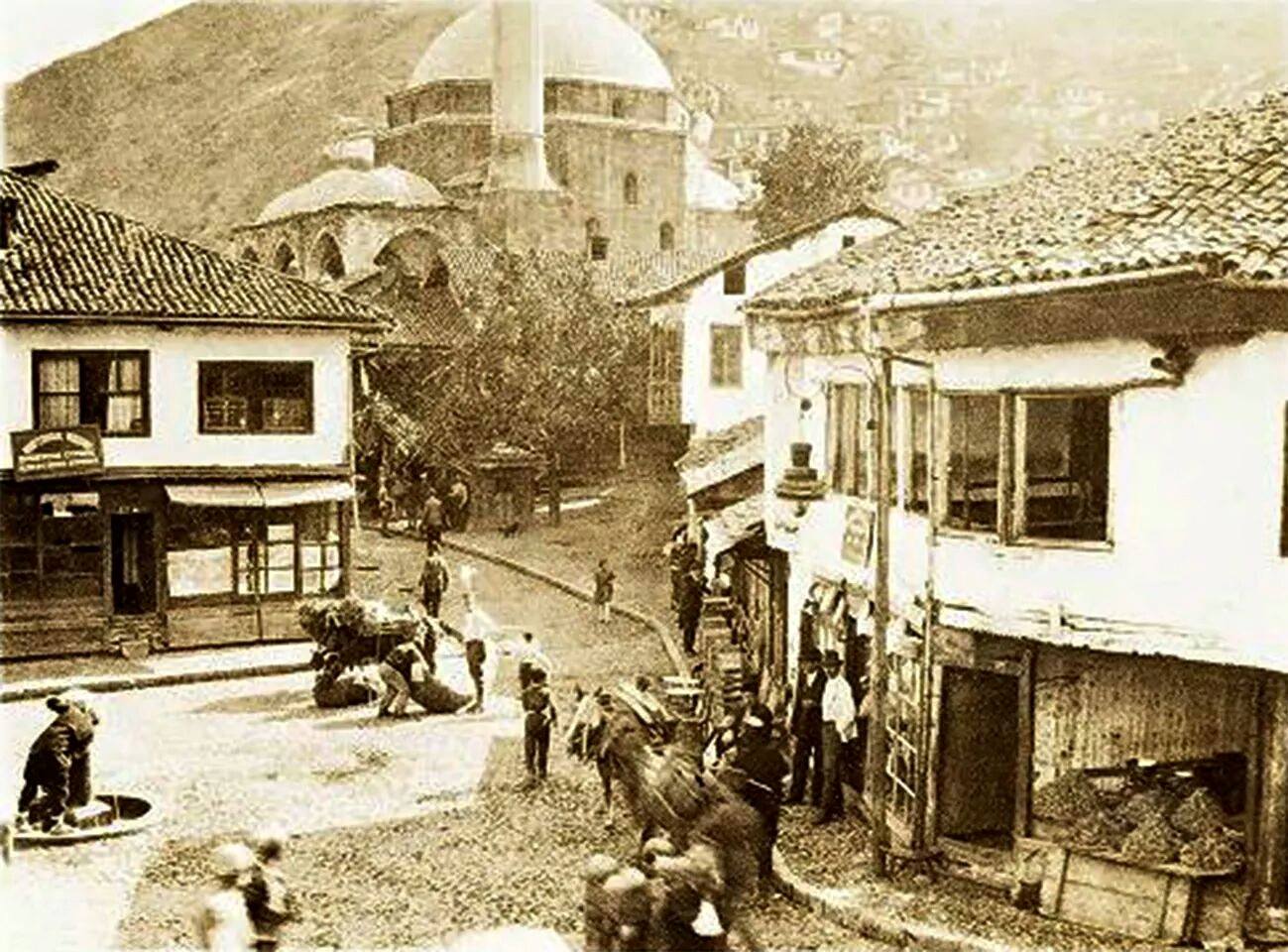

Figure 2. Old Prizren, retrieved from the archive of the Association for Culture - Plejada

Figure 2. Old Prizren, retrieved from the archive of the Association for Culture - Plejada

These neighbourhoods, known as mahallas, were characterised by a network of irregular streets, lanes, and blind alleys, which were narrow in some parts and wider in others. At the heart of urban tissue was the marketplace known as Çarshija, where citizens worked and traded. This area consisted of one-story buildings used for trading or two-story buildings with the ground floor used for trading whereas the upper floor for working, with warehouses located at the back of the shops (Fehmiu, 1971).

Figure 3. Old Prizren, Çarshia, retrieved from the archive of the Association for Culture - Plejada

Figure 3. Old Prizren, Çarshia, retrieved from the archive of the Association for Culture - Plejada

Since the 1950s, Kosovo, then part of Yugoslavia, began experiencing an economic development, which was carried out with the rural-to-urban migration among other social phenomena (Xërxa-Beqiri, 2020). This population growth brought about new demands for buildings serving various purposes educational, cultural, economic, health, and housing needs.

Figure 4. Prizren 1972, Author: Refki Cheky. Retrieved from the facebook group I love Prizren

Figure 4. Prizren 1972, Author: Refki Cheky. Retrieved from the facebook group I love Prizren

Modernist architecture in Kosovo began in the 1960s and continued until the early 1990s.2 The 1970s and early 1980s were particularly significant for architecture in Kosovo, as this period saw the most substantial investments (Jashari-Kajtazi, 2016). At this time, Kosovo was slowly transforming under the influence of modern architectural trends emerging in major cities in Yugoslavia (Gjinolli & Kabashi, 2015).

The early modernist buildings in Prizren were nonresidential buildings with diverse functions, including the Sports Center “Sezai Surroi” (1975), the Furniture Showroom “Liria” (1975), the Bus Station (1978), the Post Office, and the Commercial Center “Liria”. The first residential apartment buildings were also constructed in this time, differing from the traditional individual family houses.2

Figure 5. Commercial centre Liria Prizren. Retrieved from the facebook group I love Prizren

Figure 5. Commercial centre Liria Prizren. Retrieved from the facebook group I love Prizren

Prizren’s centre was not as heavily impacted by modernism as other cities, due to many buildings being legally protected as heritage. During the early modernist period, some buildings in the centre were demolished to make way for new ones; however, these changes were not well-received by the residents who wanted to preserve the city’s heritage. Despite this, the small city continued to grow and modernism developed more prominently in the extended parts of the city.2

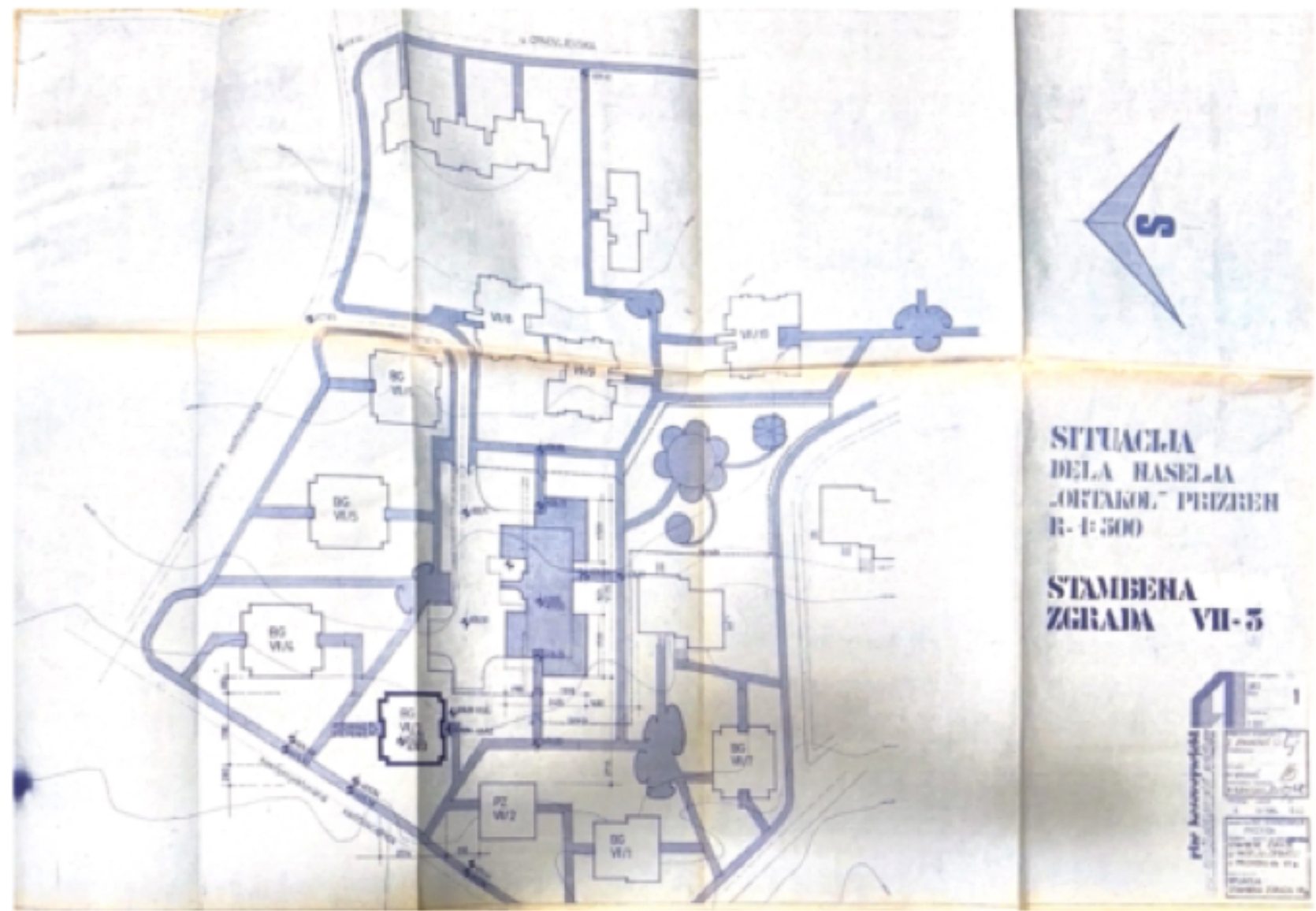

As Prizren developed, it faced a problem with informal development, which the city council attempted to address in the early 1970s (Gjinolli & Kabashi, 2015). To counter this phenomenon, the detailed plan of the Ortakoll neighbourhood was drafted in response to a request for a settlement for 7,000 residents in an open area of 50 hectares, extending the city on the northwest part (Gjinolli & Kabashi, 2015).

Ortakoll thus became the first planned neighbourhood of Prizren, one of the only two planned neighbourhoods in the city. It was drafted by Hysnije Hisari (1946-2022), the first female urbanist of Prizren. The drafting of Ortakoll began in 1970 at the Department of Urbanism at the Municipality of Prizren and was later revised by the Spatial Planning and Road Fund of Prizren in 1980-1981.3 Its construction followed shortly after (Gjinolli & Kabashi, 2015).

Figure 6. Aerial view of the residential buildings in Ortakoll. Snapshot retrieved from Google Maps in July, 2024.

Figure 6. Aerial view of the residential buildings in Ortakoll. Snapshot retrieved from Google Maps in July, 2024.

Figure 7. Master plan of the residential buildings in Ortakoll. Retrieved from the Archives of the Municipality of Prizren.

Figure 7. Master plan of the residential buildings in Ortakoll. Retrieved from the Archives of the Municipality of Prizren.

In contrast to other neighbourhoods crowded with houses and narrow roads, Ortakoll features vast green spaces, spacious playgrounds and sports courts. Surrounding these areas there are seven residential buildings with façades adorned with light yellow bricks, a common style in other cities of former Yugoslavia. Being built in the socialist time, these residential buildings were designed to provide the same living conditions, space, and natural light for all residents.2 Many people still prefer the apartments in this neighbourhood because it is well-organised and, according to old regulations, feature larger living rooms with more natural light and kitchens with windows - features not commonly found in buildings constructed under today’s regulations.2

Figure 8. Ortakoll residential buildings. Photography taken by the author in 2024.

Figure 8. Ortakoll residential buildings. Photography taken by the author in 2024.

Ortakoll features two housing typologies: residential apartment buildings and terraced family houses. The former were designed in a contemporary architecture style, ranging from five to eight stories in height, while the latter had features of regional architecture and ranged from two to three stories (Gjinolli & Kabashi, 2015). The neighbourhood's layout allocated 30% of the area for individual houses and 70% for apartment buildings, with 0.6 hectares designated for children’s playgrounds, 1 hectare for sports courts accommodating football, basketball, handball, and volleyball, and 800 square metres for commercial spaces, including four supermarkets.4

Not only was Ortakoll one of the first designed neighbourhoods, but it was also drafted by the first female urbanist of Prizren. At a time when women were largely confined to traditional roles, Hysnije Hisari stood out as a pioneer. She defied societal expectations and helped shape the city. She managed to make a combination of styles to suit the new needs of the residents but also kept traditional elements that fit in the context of the city.

Hysnije Hisari, who passed away in 2022, had a remarkable and inspiring journey, lovingly recounted by her eldest daughter, Lorika Hisari.5 Despite growing up in a society where few women were educated, with the support of her father, Hysnije Hisari graduated in 1971 with a major in urbanism at the Faculty of Architecture and Urbanism at the University of Sarajevo.6

Figure 9. Hysnije Hisari at her graduation ceremony. Photography provided by Lorika Hisari from Hysnijes personal archives.

Figure 9. Hysnije Hisari at her graduation ceremony. Photography provided by Lorika Hisari from Hysnijes personal archives.

Hisari began her professional career in 1970 at the Municipality of Prizren7 in the Department for Urbanism. Shortly after, in 1972, she was appointed the Head Town planner of the Department of Urbanism and in 1973 she began drafting the project for the Ortakoll neighbourhood (Gjinolli & Kabashi, 2015).

Figure 10. Hysnije Hisari while working during her studies. Photography provided by Lorika Hisari from Hysnijes personal archives.

Figure 10. Hysnije Hisari while working during her studies. Photography provided by Lorika Hisari from Hysnijes personal archives.

Apart from drafting the Ortakoll neighbourhood plan, Hyseni also designed other programs and plans, such as the program and urban design for the Kullat apartment building block (1971) as well as the detailed urban plan for the terraced family houses (1975), both in the Bazhdarhane neighbourhood. Additionally, she designed the program and urban design of the Sports Center - Sezai Surroi (1975) (Gjinolli & Kabashi, 2015).

Her career was distinguished by numerous awards, such as the “Bashkim Fehmiu”8 prize by the Architects Association of Kosovo for her professional contribution (2019), a certificate of appreciation by the Major of Prizren for he contribution to urbanism and architecture for Prizren (2019), as well as a certificate of appreciation from the Municipality of Prizren (2020), to her and her husband for their work on the reconstruction of the Stone Bridge in Prizren which was damaged by floods in 1979.

Residents of Ortakoll display a strong sense of community, a bond that has persisted over the years. Whether they have lived in the neighbourhood for decades or only a few years, there is a shared pride in being part of this community, even long after Ortakoll’s construction.

Through conversations and a survey of 28 residents,9 I found that the overall sentiment towards life in Ortakoll is highly positive. Among the elements of the neighbourhood with positive ratings were the green spaces, the safety of the area, connections to public transport, recreational and cultural spaces as well as the quality of the buildings. The residents mentioned some small investments on lights, benches, playgrounds and trees as some of the positive changes over the years.

Figure 11. Some of the residential buildings in Ortakoll, part of the sports court, green spaces and the entrance to the atomic shelter. Photography taken by the author in 2024.

Figure 11. Some of the residential buildings in Ortakoll, part of the sports court, green spaces and the entrance to the atomic shelter. Photography taken by the author in 2024.

However, some challenges have emerged, particularly with the neighbourhood’s growing population. This increase has led to more cars and an influx of cafés, which in turn has created issues with noise and parking. Older residents were particularly critical of changes made after 2000, feeling that the neighbourhood’s living conditions were better before these developments. Although Ortakoll was initially planned to counteract urban informal buildings, it has not been entirely immune to the negative effects of these buildings in the surrounding areas. These developments have contributed to the overcrowding of Ortakoll's recreational spaces.

A 60 year old resident, who has been living in the neighbourhood for years, expressed frustration that Ortakoll was supposed to be a residential area and it has been known as a quiet and family friendly place, but in recent years it has been transforming into a more commercial area, bringing more noise and pollution. New businesses have been criticised for usurping public green spaces, limiting their use for residents. Additionally, some of the residents were also blamed for changing the existing architecture of the residential buildings, either by constructing additional rooms or balconies to their apartments, or by usurping some of the spaces in common, such as corridors or basements.

Figure 12. Ortakoll neighbourhood sports court. Retrieved from the facebook group Ortakoll/PRIZREN.

Figure 12. Ortakoll neighbourhood sports court. Retrieved from the facebook group Ortakoll/PRIZREN.

None of the 28 residents I spoke with knew who designed their neighbourhood. The older generation attributed it vaguely to "some Serbs from the time of Yugoslavia," while the younger ones just shrugged their shoulders. This is a stark reminder of how urban spaces can evolve beyond their origins, taking on identities shaped more by the present than the past. However, the fading memory of its creator’s role invites reflection on how we, as a society, value the invisible labour of those who lay the foundations of our urban experiences.

Ortakoll represents a dialogue between past intentions and present realities. The neighbourhood embodies the complex interplay of memory, identity, and change in urban spaces while continuing to navigate the tensions between community needs and commercial pressures. In the end, perhaps the most fitting tribute to Hisari’s work isn’t just to remember her name, but to continue engaging critically with the spaces we inhabit, ensuring that the principles of thoughtful, community-centred design remain at the forefront of our urban future.

September 2024, Kosova

Get updates from balkan story map.

Building bio

NEIGHBOURHOOD BIO

Name of the neighbourhood: Ortakoll

Former name of the building/neighborhood: Ortakoll

Current Address/District: Ortakoll, Prizren

Period of design: 1981-1982

Period of construction: 1984-1985

Author/Architect/s/Urban planner: Hysnije Hisari

Institution/Architectural studio: Institute of Urbanism and Architectural Design from Prishtina

Construction company: Housing, Spatial Planning and Road Fund of Prizren

The number of buildings:7

Number of apartments: 30/per apartment